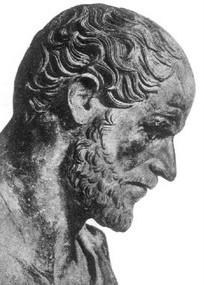

Aristotle (384 B.C.E.—322 B.C.E.)

Aristotle is a towering figure in ancient Greek philosophy, who made important contributions to logic, criticism, rhetoric, physics, biology, psychology, mathematics, metaphysics, ethics, and politics. He was a student of Plato for twenty years but is famous for rejecting Plato’s theory of forms. He was more empirically minded than both Plato and Plato’s teacher, Socrates.

Aristotle is a towering figure in ancient Greek philosophy, who made important contributions to logic, criticism, rhetoric, physics, biology, psychology, mathematics, metaphysics, ethics, and politics. He was a student of Plato for twenty years but is famous for rejecting Plato’s theory of forms. He was more empirically minded than both Plato and Plato’s teacher, Socrates.

A prolific writer, lecturer, and polymath, Aristotle radically transformed most of the topics he investigated. In his lifetime, he wrote dialogues and as many as 200 treatises, of which only 31 survive. These works are in the form of lecture notes and draft manuscripts never intended for general readership. Nevertheless, they are the earliest complete philosophical treatises we still possess.

As the father of western logic, Aristotle was the first to develop a formal system for reasoning. He observed that the deductive validity of any argument can be determined by its structure rather than its content, for example, in the syllogism: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal. Even if the content of the argument were changed from being about Socrates to being about someone else, because of its structure, as long as the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Aristotelian logic dominated until the rise of modern propositional logic and predicate logic 2000 years later.

The emphasis on good reasoning serves as the backdrop for Aristotle’s other investigations. In his natural philosophy, Aristotle combines logic with observation to make general, causal claims. For example, in his biology, Aristotle uses the concept of species to make empirical claims about the functions and behavior of individual animals. However, as revealed in his psychological works, Aristotle is no reductive materialist. Instead, he thinks of the body as the matter, and the psyche as the form of each living animal.

Though his natural scientific work is firmly based on observation, Aristotle also recognizes the possibility of knowledge that is not empirical. In his metaphysics, he claims that there must be a separate and unchanging being that is the source of all other beings. In his ethics, he holds that it is only by becoming excellent that one could achieve eudaimonia, a sort of happiness or blessedness that constitutes the best kind of human life.

Aristotle was the founder of the Lyceum, a school based in Athens, Greece; and he was the first of the Peripatetics, his followers from the Lyceum. Aristotle’s works, exerted tremendous influence on ancient and medieval thought and continue to inspire philosophers to this day.

Table of Contents

- Life and Lost Works

- Analytics or “Logic”

- Theoretical Philosophy

- Practical Philosophy

- Aristotle’s Influence

- Abbreviations

- References and Further Reading

1. Life and Lost Works

Though our main ancient source on Aristotle’s life, Diogenes Laertius, is of questionable reliability, the outlines of his biography are credible. Diogenes reports that Aristotle’s Greek father, Nicomachus, served as private physician to the Macedonian king Amyntas (DL 5.1.1). At the age of seventeen, Aristotle migrated to Athens where he joined the Academy, studying under Plato for twenty years (DL 5.1.9). During this period Aristotle acquired his encyclopedic knowledge of the philosophical tradition, which he draws on extensively in his works.

Aristotle left Athens around the time Plato died, in 348 or 347 B.C.E. One explanation is that as a resident alien, Aristotle was excluded from leadership of the Academy in favor of Plato’s nephew, the Athenian citizen Speusippus. Another possibility is that Aristotle was forced to flee as Philip of Macedon’s expanding power led to the spread of anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens (Chroust 1967). Whatever the cause, Aristotle subsequently moved to Atarneus, which was ruled by another former student at the Academy, Hermias. During his three years there, Aristotle married Pythias, the niece or adopted daughter of Hermias, and perhaps engaged in negotiations or espionage on behalf of the Macedonians (Chroust 1972). Whatever the case, the couple relocated to Macedonia, where Aristotle was employed by Philip, serving as tutor to his son, Alexander the Great (DL 5.1.3–4). Aristotle’s philosophical career was thus directly entangled with the rise of a major power.

After some time in Macedonia, Aristotle returned to Athens, where he founded his own school in rented buildings in the Lyceum. It was presumably during this period that he authored most of his surviving texts, which have the appearance of lecture transcripts edited so they could be read aloud in Aristotle’s absence. Indeed, this must have been necessary, since after his school had been in operation for thirteen years, he again departed from Athens, possibly because a charge of impiety was brought against him (DL 5.1.5). He died at age 63 in Chalcis (DL 5.1.10).

Diogenes tells us that Aristotle was a thin man who dressed flashily, wearing a fashionable hairstyle and a number of rings. If the will quoted by Diogenes (5.1.11–16) is authentic, Aristotle must have possessed significant personal wealth, since it promises a furnished house in Stagira, three female slaves, and a talent of silver to his concubine, Herpyllis. Aristotle fathered a daughter with Pythias and, with Herpyllis, a son, Nicomachus (named after his grandfather), who may have edited Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Unfortunately, since there are few extant sources on Aristotle’s life, one’s judgment about the accuracy and completeness of these details depends largely on how much one trusts Diogenes’ testimony.

Since commentaries on Aristotle’s work have been produced for around two thousand years, it is not immediately obvious which sources are reliable guides to his thought. Aristotle’s works have a condensed style and make use of a peculiar vocabulary. Though he wrote an introduction to philosophy, a critique of Plato’s theory of forms, and several philosophical dialogues, these works survive only in fragments. The extant Corpus Aristotelicum consists of Aristotle’s recorded lectures, which cover almost all the major areas of philosophy. Before the invention of the printing press, handwritten copies of these works circulated in the Near East, northern Africa, and southern Europe for centuries. The surviving manuscripts were collected and edited in August Immanuel Bekker’s authoritative 1831–1836 Berlin edition of the Corpus (“Bekker” 1910). All references to Aristotle’s works in this article follow the standard Bekker numbering.

The extant fragments of Aristotle’s lost works, which modern commentators sometimes use as the basis for conjectures about his philosophical development, are noteworthy. A fragment of his Protrepticus preserves a striking analogy according to which the psyche or soul’s attachment to the body is a form of punishment:

The ancients blessedly say that the psyche pays penalty and that our life is for the atonement of great sins. And the yoking of the psyche to the body seems very much like this. For they say that, as Etruscans torture captives by chaining the dead face to face with the living, fitting each to each part, so the psyche seems to be stretched throughout, and constrained to all the sensitive members of the body. (Pistelli 1888, 47.24–48.1)

According to this allegedly inspired theory, the fetters that bind the psyche to the body are similar to those by which the Etruscans torture their prisoners. Just as the Etruscans chain prisoners face to face with a dead body so that each part of the living body touches a part of the corpse, the psyche is said to be aligned with the parts of one’s living body. On this view, the psyche is embodied as a painful but corrective atonement for its badness. (See Bos 2003 and Hutchinson and Johnson’s webpage).

The incompatibility of this passage with Aristotle’s view that the psyche is inseparable from the body (discussed below) has been explained in various ways. Neo-Platonic commentators distinguish between Aristotle’s esoteric and exoteric writings, that is, writings intended for circulation within his school, and writings like the Protrepticus intended for a broader reading public (Gerson 2005, 47–75). Some modern scholars have argued to the contrary that the imprisonment of the psyche in the body indicates that Aristotle was still a Platonist at the time he composed the Protrepticus, which must have been written earlier than his mature works (Jaeger 1948, 100). Aristotle’s dialogue Eudemus, which contains arguments for the immortality of the psyche, and his Politicus, which is about the ideal statesman, seem to corroborate the view that Aristotle’s exoteric works hold much that is Platonic in spirit (Chroust 1965; 1966). The latter contains the seemingly Platonic assertion that “the good is the most exact of measures” (Kroll 1902, 168: 927b4–5).

But not all agree. Owen (1968, 162–163) argues that Aristotle’s fundamental logical distinction between individual and species depends on an antecedent break with Plato. According to this view, Aristotle’s On Ideas (Fine 1993), a collection of arguments against Platonic forms, shows that Aristotle rejected Platonism early in his career, though he later became more sympathetic to the master’s views. However, as Lachterman (1980) points out, such historical theses depend on substantive hermeneutical assumptions about how to read Aristotle and on theoretical assumptions about what constitutes a philosophical system. This article focuses not on this historical debate but on the theories propounded in Aristotle’s extant works.

2. Analytics or “Logic”

Aristotle is usually identified as the founder of logic in the West (although autonomous logical traditions also developed in India and China), where his “Organon,” consisting of his works the Categories, On Interpretation, Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Sophistical Refutations, and Topics, long served as the traditional manuals of logic. Two other works—Rhetoric and Poetics—are not about logic, but also concern how to communicate to an audience. Curiously, Aristotle never used the words “logic” or “organon” to refer to his own work but calls this discipline “analytics.” Though Aristotelian logic is sometimes referred to as an “art” (Ross 1940, iii), it is clearly not an art in Aristotle’s sense, which would require it to be productive of some end outside itself. Nevertheless, this article follows the convention of referring to the content of Aristotle’s analytics as “logic.”

a. The Meaning and Purpose of Logic

What is logic for Aristotle? On Interpretation begins with a discussion of meaning, according to which written words are symbols of spoken words, while spoken words are symbols of thoughts (Int.16a3–8). This theory of signification can be understood as a semantics that explains how different alphabets can signify the same spoken language, while different languages can signify the same thoughts. Moreover, this theory connects the meaning of symbols to logical consequence, since commitment to some set of utterances rationally requires commitment to the thoughts signified by those utterances and to what is entailed by them. Hence, though Cook Wilson (1926, 30–33) correctly notes that Aristotle nowhere defines logic, it may be called the science of thinking, where the role of the science is not to describe ordinary human reasoning but rather to demonstrate what one ought to think given one’s other commitments. Though the elements of Aristotelian logic are implicit in our conscious reasoning, Aristotelian “analysis” makes explicit what was formerly implicit (Cook Wilson 1926, 49).

Aristotle shows how logic can demonstrate what one should think, given one’s commitments, by developing the syntactical concepts of truth, predication, and definition. In order for a written sentence, utterance, or thought to be true or false, Aristotle says, it must include at least two terms: a subject and a predicate. Thus, a simple thought or utterance such as “horse” is neither true nor false but must be combined with another term, say, “fast” in order to form a compound—“the horse is fast”—that describes reality truly or falsely. The written sentence “the horse is fast” has meaning insofar as it signifies the spoken sentence, which in turn has meaning in virtue of its signifying the thought that the horse is fast (Int.16a10–18, Cat.13b10–12, DA 430a26–b1). Aristotle holds that there are two kinds of constituents of meaningful sentences: nouns and their derivatives, which are conventional symbols without tense or aspect; and verbs, which have a tense and aspect. Though all meaningful speech consists of combinations of these constituents, Aristotle limits logic to the consideration of statements, which assert or deny the presence of something in the past, present, or future (Int.17a20–24).

Aristotle analyzes statements as cases of predication, in which a predicate P is attributed to a subject S as in a sentence of the form “S is P.” Since he holds that every statement expresses something about being, statements of this form are to be read as “S is (exists) as a P” (Bäck 2000, 11). In every true predication, either the subject and predicate are of the same category, or the subject term refers to a substance while the predicate term refers to one of the other categories. The primary substances are individuals, while secondary substances are species and genera composed of individuals (Cat.2a11–18). This distinction between primary and secondary reflects a dependence relation: if all the individuals of a species or genus were annihilated, the species and genus could not, in the present tense, be truly predicated of any subject.

Every individual is of a species and that species is predicated of the individual. Every species is the member of a genus, which is predicated of the species and of each individual of that species (Cat.2b13–22). For example, if Callias is of the species “man,” and the species is a member of the genus “animal,” then “man” is predicated of Callias, and “animal” is predicated both of “man” and of Callias. The individual, Callias, inherits the predicate “animal” in virtue of being of the species “man.” But inheritance stops at the individual and does not apply to its proper parts. For example, “man” is not truly predicated of Callias’ hand. A genus can be divided with reference to the specific differences among its members; for example, “biped” differentiates “man” from “horse.”

While no definition can be given of an individual or primary substance such as Callias, when one gives the genus and all the specific differences possessed by a kind of thing, one can define a thing’s species. A specific difference is a predicate that falls under one of the categories. Thus, Aristotelian categories can be seen as a taxonomical scheme, a way of organizing predicates for discovery, or as a metaphysical doctrine about the kinds of beings there are. But any reading must accommodate Aristotle’s views that primary substances are never predicated of a subject (Cat.3a6), that a predicate may fall under multiple categories (Cat.11a20–39), and that some terms, such as “good,” are predicated in all the categories (NE 1096a23–29). Moreover, definitions are reached not by demonstration but by other kinds of inquiry, such as dialectic, the art by which one makes divisions in a genus; and induction, which can reveal specific differences from the observation of individual examples.

b. Demonstrative Syllogistic

Syllogistic reasoning builds on Aristotle’s theory of predication, showing how to reason from premises to conclusions. A syllogism is a discourse in which when taking some statements as premises a different statement can be shown to follow as a conclusion (AnPr.24b18–22). The basic form of the Aristotelian syllogism involves a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion, so that it has the form

If A is predicated of all B,

And B is predicated of all C,

Then A is predicated of all C.

This is an assertion of formal logic, since by removing the values of the variables A, B, and C, one treats the inference formally, such that the values of the subject A and predicates B and C are not given as part of the syllogistic form (Łukasiewicz, 10–14).

Though this form can be utilized in dialectic, in which the major term A is related to C through the middle term B credibly rather than necessarily (AnPo.81b10–23), Aristotle is mainly concerned with how to use syllogistic in what he calls demonstrative reasoning, that is, in inference from certain premises to a certain conclusion. A demonstrative syllogism is not concerned with a mere opinion but proves a cause, that is, answers a “why” question (AnPo.85b 23–26).

The validity of a syllogism can be tested through comparison of four basic types of assertions: All S are P (A), No S are P (E), Some S are P (I), and Some S are not P (O). The truth conditions of these assertions are determined relationally: through contradiction, in which if one of the assertions is true, the other must be false; contrariety, in which both assertions cannot be true; and subalternation, in which the universal assertion’s being true requires that the particular assertion must be true, as well. These relationships are summed up in the traditional square of opposition used by medieval Aristotelian logicians. (see Groarke, Aristotle: Logic).

Figure 1: The Traditional Square of Opposition illustrates the relations between the fundamental judgment-forms in Aristotelian syllogistic: (A) All S are P, (E) No S are P, (I) Some S are P, and (O) Some S are not P.

Syllogistic may be employed dialectically when the premises are accepted on the authority of common opinion, from tradition, or from the wise. In any dialectical syllogism, the premises can be generally accepted opinions rather than necessary principles (Top.100a25–b21). At least some premises in rhetorical proofs must be not necessary but only probable, happening only for the most part.

When the premises are known, and conclusions are shown to follow from those premises, one gains knowledge by demonstration. Demonstration is necessary (AnPo.73a21–27) because the conclusion of a demonstrative syllogism predicates something that is either necessarily true or necessarily false of the subject of the premise. One has demonstrative knowledge when one knows the premises and has derived a necessary conclusion from them, since the cause given in the premises explains why the conclusion is so (AnPo.75a12–17, 35–37). Consequently, valid demonstration depends on the known premises containing terms for the genus of which the species in the conclusion is a member (AnPo.76a29–30).

One interesting problem that arises within Aristotle’s theory of demonstration concerns the connection between temporality and necessity. By the principle of excluded middle, necessarily, either there will be a sea-battle tomorrow or there will not be a sea-battle tomorrow. But since the sea-battle itself has yet neither come about nor failed to come about, it seems that one must say, paradoxically, that one alternative is necessary but that either alternative might come about (Int.19a22–34). The question of how to account for unrealized possibilities and necessities is part of Aristotle’s modal syllogistic, which is discussed at length in his Prior Analytics. For a discussion, see Malink (2013).

c. Induction, Experience, and Principles

Whenever a speaker reasons from premises, an auditor can ask for their demonstration. The speaker then needs to adduce additional premises for that demonstration. But if this line of questioning went on interminably, no demonstration could be made, since every premise would require a further demonstration, ad infinitum. In order to stop an infinite regress of premises, Aristotle postulates that for an inference to count as demonstrative, one must know its indemonstrable premises (AnPo.73a16–20). Thus, demonstrative science depends on the view that all teaching and learning proceed from already present knowledge (AnPo.72b5–20). In other words, the possibility of making a complete argument, whether inductive or deductive, depends on the reasoner possessing the concept in question.

The acquisition of concepts must in some way be perceptual, since Aristotle says that universals come to rest in the soul through experience, which comes about from many memories of the same thing, which in turn comes about by perception (AnPo.99b32–100a9). However, Aristotle holds that some concepts are already manifested in one’s perceptual experience: children initially call all men father and all women mother, only later developing the capacity to apply the relevant concepts to particular individuals (Phys.184b3–5). As Cook Wilson (1926, 45) puts it, perception is in a way already of a universal. Upon learning to speak, the child already possesses the concept “mother” but does not grasp the conditions of its correct application. The role of perception, and hence of memory and experience, is then not to supply the child with universal concepts but to fix the conditions under which they are correctly predicated of an individual or species. Hence the ability to arrive at definitions, which serve as starting points of a science, rests on the human being’s natural capacity to use language and on the culturally specific social and political conditions in which that capacity is manifested (Winslow 2013, 45–49).

While deduction proceeds by a form of syllogistic reasoning in which the major and minor premise both predicate what is necessarily true of a subject, inductive reasoning moves from particulars to universals, so it is impossible to gain knowledge of universals except by induction (AnPo.81a38–b9). This movement, from the observation of the same occurrence, to an experience that emerges from many memories, to a universal judgment, is a cognitive process by which human beings understand reality (see AnPo.88a2–5, Met.980b28–981a1, EN 1098b2–4, 1142a12).

But what makes such an inference a good one? Aristotle seems to say an inductive inference is sound when what is true in each case is also true of the class under which the cases fall (AnPr.68b15–29). For example, it is inferred from the observation that each kind of bileless animal (men, horses, mules, and so on) is long-lived just when the following syllogism is sound: (1) All men, horses, mules, and so on are long-lived; (2) All long-lived animals are bileless; therefore (3) all men, horses, mules, and so on are bileless (see Groarke sections 10 and 11). However, Aristotle does not think that knowledge of universals is pieced together from knowledge of particulars but rather he thinks that induction is what allows one to actualize knowledge by grasping how the particular case falls under the universal (AnPr.67a31–b5).

A true definition reveals the essential nature of something, what it is to be that thing (AnPo.90b30–31). A sound demonstration shows what is necessary of an observed subject (AnPo.90b38–91a5). It is essential, however, that the observation on which a definition is based be inductively true, that is, that it be based on causes rather than on chance. Regardless of whether one is asking what something is in a definition or why something is the way it is by giving its cause, it is only when the principles or starting points of a science are given that demonstration becomes possible. Since experience is what gives the principles of each science (AnPr.46a17–27), logic can only be employed at a later stage to demonstrate conclusions from these starting points. This is why logic, though it is employed in all branches of philosophy, is not a part of philosophy. Rather, in the Aristotelian tradition, logic is an instrument for the philosopher, just as a hammer and anvil are instruments for the blacksmith (Ierodiakonou 1998).

d. Rhetoric and Poetics

Just as dialectic searches for truth, Aristotelian rhetoric serves as its counterpart (Rhet.1354a1), searching for the means by which truth can be grasped through language. Thus, rhetorical demonstration, or enthymeme, is a kind of syllogism that strictly speaking belongs to dialectic (Rhet.1355a8–10). Because rhetoric uses the particularly human capacity of reason to formulate verbal arguments, it is the art that can cause the most harm when it is used wrongly. It is thus not a technique for persuasion at any cost, as some Sophists have taught, but a fundamentally second-personal way of using language that allows the auditor to reach a judgment (Grimaldi 1972, 3–5). More fundamentally, rhetoric is defined as the detection of persuasive features of each subject matter (Rhet.1355b12–22).

Proofs given in speech depend on three things: the character (ethos) of the speaker, the disposition (pathos) of the audience, and the meaning (logos) of the sounds and gestures used (Rhet.1356a2–6). Rhetorical proofs show that the speaker is worthy of credence, producing an emotional state (pathos) in the audience, or demonstrating a consequence using the words alone. Aristotle holds that ethos is the most important of these elements, since trust in the speaker is required if one is to believe the speech. However, the best speech balances ethos, pathos, and logos. In rhetoric, enthymemes play a deductive role, while examples play an inductive role (Rhet.1356b11–18).

The deductive form of rhetoric, enthymeme, is a dialectical syllogism in which the probable premise is suppressed so that one reasons directly from the necessary premise to the conclusion. For example, one may reason that an animal has given birth because she has milk (Rhet.1357b14–16) without providing the intermediate premise. Aristotle also calls this deductive form of inference “reasoning by signs” or “reasoning from evidence,” since the animal’s having milk is a sign of, or evidence for, her having given birth. Though the audience seemingly “immediately” grasps the fact of birth without it being given in perception, the passage from the perception to the fact is inferential and depends on the background assumption of the suppressed premise.

The inductive form of rhetoric, reasoning from example, can be illustrated as follows. Peisistratus in Athens and Theagenes in Megara both petitioned for guards shortly before establishing themselves as tyrants. Thus, someone plotting a tyranny requests a guard (Rhet.1357b30–37). This proof by example does not have the force of necessity or universality and does not count as a case of scientific induction, since it is possible someone could petition for a guard without plotting a tyranny. But when it is necessary to base some decision, for example, whether to grant a request for a bodyguard, on its likely outcome, one must look to prior examples. It is the work of the rhetorician to know these examples and to formulate them in such a way as to suggest definite policies on the basis of that knowledge.

Rhetoric is divided into deliberative, forensic, and display rhetoric. Deliberative rhetoric is concerned with the future, namely with what to do, and the deliberative rhetorician is to discuss the advantages and harms associated with a specific course of action. Forensic rhetoric, typical of the courtroom, concerns the past, especially what was done and whether it was just or unjust. Display rhetoric concerns the present and is about what is noble or base, that is, what should be praised or denigrated (Rhet.1358b6–16). In all these domains, the rhetorician practices a kind of reasoning that draws on similarities and differences to produce a likely prediction that is of value to the political community.

A common characteristic of insightful philosophers, rhetoricians, and poets is the capacity to observe similarities in things that are unlike, as Archytas did when he said that a judge and an alter are kindred, since someone who has been wronged has recourse to both (Rhet.1412a10–14). This noticing of similarities and differences is part of what separates those who are living the good life from those who are merely living (Sens.437a2–3). Likewise, the highest achievement of poetry is to use good metaphors, since to make metaphors well is to contemplate what is like (Poet.1459a6–9). Poetry is thus closely related to both philosophy and rhetoric, though it differs from them in being fundamentally mimetic, imitating reality through an artistic form.

Imitation in poetry is achieved by means of rhythm, language, and harmony (Poet.1447a13–16, 21–22). While other arts share some or all these elements—painting imitates visually by the same means, while dance imitates only through rhythm—poetry is a kind of vocalized music, in which voice and discursive meaning are combined. Aristotle is interested primarily in the kinds of poetry that imitate human actions, which fall into the broad categories of comedy and tragedy. Comedy is an imitation of worse types of people and actions, which reflect our lower natures. These imitations are not despicable or painful, but simply ridiculous or distorted, and observing them gives us pleasure (Poet.1449a31–38). Aristotle wrote a book of his Poetics on comedy, but the book did not survive. Hence, through a historical accident, the traditions of aesthetics and criticism that proceed from Aristotle are concerned almost completely with tragedy.

Tragedy imitates actions that are excellent and complete. As opposed to comedy, which is episodic, tragedy should have a single plot that ends in a presentation of pity and fear and thus a catharsis—a cleansing or purgation—of the passions (Poet.1449b24–28). (As discussed below, the passions or emotions also play an important role in Aristotle’s practical philosophy.) The most important aspect of a tragedy is how it uses a story or myth to lead the psyches of its audience to this catharsis (Poet.1450a32–34). Since the beauty or fineness of a thing—say, of an animal—consists in the orderly arrangement of parts of a definite magnitude (Poet.1450b35–38), the parts of a tragedy should also be proportionate.

A tragedy’s ability to lead the psyche depends on its myth turning at a moment of recognition at which the central character moves from a state of ignorance to a state of knowledge. In the best case, this recognition coincides with a reversal of intention, such as in Sophocles’ Oedipus, in which Oedipus recognizes himself as the man who was prophesied to murder his father and marry his mother. This moment produces pity and fear in the audience, fulfilling the purpose of tragic imitation (Poet.1452a23–b1). The pity and fear produced by imitative poetry are the source of a peculiar form of pleasure (Poet.1453b11–14). Though the imitation itself is a kind of technique or art, this pleasure is natural to human beings. Because of this potential to produce emotions and lead the psyche, poetics borders both on what is well natured and on madness (Poet.1455a30–34).

Why do people write plays, read stories, and watch movies? Aristotle thinks that because a series of sounds with minute differences can be strung together to form conventional symbols that name particular things, hearing has the accidental property of supporting meaningful speech, which is the cause of learning (Sens.437a10–18). Consequently, though sound is not intrinsically meaningful, voice can carry meaning when it “ensouled,” transmitting an appearance about how absent things might be (DA 420b5-10, 27–33). Poetry picks up on this natural capacity, artfully imitating reality in language without requiring that things are actually the way they are presented as being (Poet.1447a13–16).

The poet’s consequent power to lead the psyche through true or false imitations, like the rhetorician’s power to lead it through persuasive speech, leads to a parallel question: how should the poet use his power? Should the poet imitate things as they are, or as they should be? Though it is clear that the standard of correctness in poetry and politics is not the same (Poet.1460b13–1461a1), the question of how and to what extent the state should constrain poetic production remains unresolved.

3. Theoretical Philosophy

Aristotle’s classification of the sciences makes a distinction between theoretical philosophy, which aims at contemplation, and practical philosophy, which aims at action or production. Within theoretical philosophy, first philosophy studies objects that are motionless and separate from material things, mathematics studies objects that are motionless but not separate, and natural philosophy studies objects that are in motion and not separate (Met.1026a6–22).

This threefold distinction among the beings that can be contemplated corresponds to the level of precision that can be attained by each branch of theoretical philosophy. First philosophy can be perfectly exact because there is no variation among its objects and thus it has the potential to give one knowledge in the most profound sense. Mathematics is also absolutely certain because its objects are unchanging, but since there are many mathematical objects of a given kind (for example, one could draw a potentially infinite number of different triangles), mathematical proofs require a peculiar method that Aristotle calls “abstraction.” Natural philosophy gives less exact knowledge because of the diversity and variability of natural things and thus requires attention to particular, empirical facts. Studies of nature—including treatises on special sciences like cosmology, biology, and psychology—account for a large part of Aristotle’s surviving writings.

a. Natural Philosophy

Aristotle’s natural philosophy aims for theoretical knowledge about things that are subject to change. Whereas all generated things, including artifacts and products of chance, have a source that generates them, natural change is caused by a thing’s inner principle and cause, which may accordingly be called the thing’s “nature” (Phys.192b8–20). To grasp the nature of a thing is to be able to explain why it was generated essentially: the nature of a thing does not merely contribute to a change but is the primary determinant of the change as such (Waterlow 1982, p.28).

Though some hold that Aristotle’s principles are epistemic, explanatory concepts, principles are best understood ontologically as unique, continuous natures that govern the generation and self-preservation of natural beings. To understand a thing’s nature is primarily to grasp “how a being displays itself by its nature.” Such a grasp counts as a correct explanation only insofar as it constitutes a form of understanding of beings in themselves as they give themselves (Winslow 2007, 3–7).

Aristotle’s description of principles as the start and end of change (Phys.235b6) distinguishes between two kinds of natural change. Substantial change occurs when a substance is generated (Phys.225a1–5), for example, when the seed of a plant gives rise to another plant of the same kind. Non-substantial change occurs when a substance’s accidental qualities are affected, for example, the change of color in a ripening pomegranate. Aristotelians describe this as the activity of contraries of blackness and whiteness in the plant’s material in which the fruit of the pomegranate, as its juices become colored by ripening, itself becomes shaded, changing to a purple color (de Coloribus 796a20–26). Ripening occurs when heat burns up the air in the part of the plant near the ground, causing convection that alters the originally light color of the fruit to its dark contrary (de Plantis 820b19–23). Both kinds of change are caused by the plant’s containing in itself a principle of change. In substantial change, a new primary substance is generated; in non-substantial change, some property of preexisting substance changes to a contrary state.

A process of change is completely described when its four causes are given. This can be illustrated with Aristotle’s favorite example of the production of a bronze sculpture. The (1) material cause of the change is given when the underlying matter of the thing has been described, such as the bronze matter of which a statue is composed. The (2) formal cause is given when one says what kind of thing the thing is, for example, “sphere” for a bronze sphere or “Callias” for a bronze statue of Callias. The (3) efficient cause is given when one says what brought the change about, for example, when one names the sculptor. The (4) final cause is given when one says the purpose of the change, for example, when one says why the sculptor chose to make the bronze sphere (Phys.194b16–195a2).

In natural change the principle of change is internal, so the formal, efficient, and final causes typically coincide. Moreover, in such cases, the metaphysical and epistemological sides of causal explanation are normally unified: a formal cause counts both as a thing’s essence—what it is to be that thing—and as its rational account or reason for being (Bianchi 2014, 35). Thus, when speaking of natural changes rather than the making of an artifact, Aristotle will usually offer “hylomorphic” descriptions of the natural being as a compound of matter and form.

Because Aristotle holds that a thing’s underlying nature is analogous to the bronze in a statue (Phys.191a7–12), some have argued that the underlying thing refers to “prime matter,” that is, to an absolutely indeterminate matter that has no form. But Cook (1989) has shown that the underlying thing normally means matter that already has some form. Indeed, Aristotle claims that the matter of perceptible things has no separate existence but is always already informed by a contrary (Gen et Corr.329a25–27). The matter that traditional natural philosophy calls the “elements”—fire, water, air, and earth—already has the form of the basic contraries, hot and cold, and moist and dry, so that, for example, fire is matter with a hot and dry form (Gen et Corr.330a25–b4). Thus, even in the most basic cases, matter is always actually informed, even though the form is potentially subject to change. For example, throwing water on a fire cools and moistens it, and bringing about a new quality in the underlying material. Thus, Aristotle sometimes describes natural powers as being latent or active “in the material” (Meteor.370b14–18).

Aristotle’s general works in natural philosophy offer analyses of concepts necessarily assumed in accounts of natural processes, including time, change, and place. In general, Aristotle will describe changes that occur in time as arising from a potential, which is actualized when the change is complete. However, what is actual is logically prior to what is potential, since a potentiality aims at its own actualization and thus must be defined in terms of what is actual. Indeed, generically the actual is also temporally prior to potentiality, since there must invariably be a preexisting actuality that brings the potentiality to its own actualization (Met.1049b4–19). Perhaps because of the priority of the actual to the potential, whenever Aristotle speaks of natural change, he is concerned with a field of naturalistic inquiry that is continuous rather than atomistic and purposeful or teleological rather than mechanical. In his more specific naturalistic works, Aristotle lays out a program of specialized studies about the heavens and Earth, living things, and the psyche.

i. Cosmology and Geology

Aristotle’s cosmology depends on the basic observation that while bodies on Earth either rise to a limit or fall to Earth, heavenly bodies keep moving, without any apparent external force being exerted on them (DC 284a10–15). On the basis of this observation, he distinguishes between circular motion, which is operative in the “superlunary” heavens, and rectilinear motion on “sublunary” Earth below the Moon. Since all sublunary bodies move in a rectilinear pattern, the heavenly bodies must be composed of a different body that naturally moves in a circle (DC 269a2–10, Meteor.340b6–15). This body cannot have an opposite, because there is no opposite to circular motion (DC 270a20, compare 269a19–22). Indeed, since there is nothing to oppose its motion, Aristotle supposes that this fifth element, which he calls “aether,” as well as the heavenly bodies composed of it, move eternally (DC 275b1–5, 21–25).

In Aristotle’s view the heavens are ungenerated, neither coming to be nor passing away (DC 279b18–21, 282a24–30). Aristotle defines time as the number of motion, since motion is necessarily measured by time (Phys.224a24). Thus, the motion of the eternal bodies is what makes time, so the life and being of sublunary things depends on them. Indeed, Aristotle says that their own time is eternal or “aeon.”

Noticing that water naturally forms spherical droplets and that it flows towards the lowest point on a plane, Aristotle concludes that both the heavens and the earth are spherical (DC 287b1–14). This is further confirmed by observations of eclipses (DC 297b23–31) and that different stars are visible at different latitudes (DC 297b14–298a22).

The gathering of such observations is an important part of Aristotle’s scientific procedure (AnPr.46a17–22) and sets his theories above those of the ancients that lacked such “experience” (Phys.191a24–27). Just as in his biology, where Aristotle draws on animal anatomy observed at sacrifices (HA 496b25) and records reports from India (HA 501a25), so in his astronomy he cites Egyptian and Babylonian observations of the planets (DC 292a4–9). By gathering evidence from many sources, Aristotle is able to conclude that the stars and the Moon are spherical (DC 291b11–20) and that the Milky Way is an appearance produced by the sight of many stars moving in the outermost sphere (Meteor.346a16–24).

Assuming the hypothesis that the Earth does not move (DC 289b6–7), Aristotle argues that there are in the heavens both stars, which are large and distant from earth, and planets, which are smaller and closer. The two can be distinguished since stars appear to twinkle while planets do not (Aristotle somewhat mysteriously attributes the twinkling stars to their distance from the eye of the observer) (DC 290b14–24). Unlike earthly creatures, which move because of their distinct organs or parts, both the moving stars and the unmoving heaven that contains them are spherical (DC 289a30–b11). As opposed to superlunary (eternal) substances, sublunary beings, like clouds and human beings, participate in the eternal through coming to be and passing away. In doing so, the individual or primary substance is not preserved, but rather the species or secondary substance is preserved (as we shall see below, the same thought is utilized in Aristotle’s explanation of biological reproduction) (Gen et Corr.338b6–20).

Aristotle holds that the Earth is composed of four spheres, each of which is dominated by one of the four elements. The innermost and heaviest sphere is predominantly earth, on which rests upper spheres of water, air, and fire. The sun acts to burn up or vaporize the water, which rises to the upper spheres when heated, but when cooled later condenses into rain (Meteor.354b24–34). If unqualified necessity is restricted to the superlunary sphere, teleology—the seeking of ends that may or may not be brought about—seems to be limited to the sublunary sphere.

Due to his belief that the Earth is eternal, being neither created nor destroyed, Aristotle holds that the epochs move cyclically in patterns of increase and decrease (Meteor.351b5–19). Aristotle’s cyclical understanding of both natural and human history is implicit in his comment that while Egypt used to be a fertile land, it has over the centuries grown arid (Meteor.351b28–35). Indeed, parts of the world that are ocean periodically become land, while those that are land are covered over by ocean (Meteor.253a15–24). Because of periodic catastrophes, all human wisdom that is now sought concerning both the arts and divine things was previously possessed by forgotten ancestors. However, some of this wisdom is preserved in myths, which pass on knowledge of the divine by allegorically portraying the gods in human or animal form so that the masses can be persuaded to follow laws (Met.1074a38-b14, compare Meteor.339b28–30, Pol.1329b25).

Aristotle’s geology or earth science, given in the latter books of his Meteorology, offers theories of the formation of oceans, of wind and rainfall, and of other natural events such as earthquakes, lightning, and thunder. His theory of the rainbow suggests that drops of water suspended in the air form mirrors which reflect the multiply-colored visual ray that proceeds from the eye without its proper magnitude (Meteor.373a32–373b34). Though the explanations given by Aristotle of these phenomena contradict those of modern physics, his careful observations often give interest to his account.

Aristotle’s material science offers the first description of what are now called non-Newtonian fluids—honey and must—which he characterizes as liquids in which earth and heat predominate (Meteor.385b1–5). Although the Ancient Greeks did not distill alcohol, he reports on the accidental distillation of some ethanol from wine (“sweet wine”), which he observes is more combustible than ordinary wine (Meteor.387b10–14). Finally, Aristotle’s material science makes an informative distinction between compounds, in which the constituents maintain their identity, and mixtures, in which one constituent comes to dominate or in which a new kind of material is generated (see Sharvy 1983 for discussion). Though it would be inaccurate to describe him as a methodological empiricist, Aristotle’s collection and careful recording of observations shows that in all of his scientific endeavors, his explanations were designed to accord with publicly observable natural phenomena.

ii. Biology

The phenomenon of life, as opposed to inanimate nature, involves distinctive types of change (Phys.244b10–245a5) and thus requires distinctive types of explanation. Biological explanations should give all four causes of an organism or species—the material of which it is composed, the processes that bring it about, the particular form it has, and its purpose. For Aristotle, the investigation of individual organisms gives one causal knowledge since the individuals belong to a natural kind. Men and horses both have eyes, which serve similar functions in each of them, but because their species are different, a man’s eye is similar to the eyes of other men, while a horse’s eyes are similar to the eyes of other horses (HA 486a15–20). Biology should explain both why homologous forms exist in different species and the ways in which they differ, and therefore the causes for the persistence of each natural kind of living thing.

Although all four causes are relevant in biology, Aristotle tends to group final causes with formal causes in teleological explanations, and material causes with efficient causes in mechanical explanations. Boylan (section 4) shows, for example, that Aristotle’s teleological explanation of respiration is that it exists in order to bring air into the body to produce pneuma, which is the means by which an animal moves itself. Aristotle’s mechanical explanation is that air that has been heated in the lungs is pushed out by colder air outside the body (On Breath 481b10–16, PA 642a31–b4).

Teleological explanations are necessary conditionally; that is, they depend on the assumption that the biologist has correctly identified the end for the sake of which the organism behaves as it does. Mechanical explanations, in distinction, have absolute necessity in the sense that they require no assumptions about the purpose of the organism or behavior. In general, however, teleological explanations are more important in biology (PA 639b24–26), because making a distinction between living and inanimate things depends on the assumption that “nature does nothing in vain” (GA 741b5).

The final cause of each kind corresponds to the reason that it continues to persist. As opposed to superlunary, eternal substances, sublunary living things cannot preserve themselves individually or, as Aristotle puts it, “in number.” Nevertheless, because living is better than not living (EN 1170b2–5), each individual has a natural drive to preserve itself “in kind.” Such a drive for self-preservation is the primary way in which living creatures participate in the divine (DA 415a25–b7). Nutrition and reproduction therefore are, in Aristotle’s philosophy, value-laden and goal-directed activities. They are activated, whether consciously or not, for the good of the species, namely for its continuation, in which it imitates the eternal things (Gen et Corr.338b12–17). In this way, life can be considered to be directed toward and imitative of the divine (DC 292b18–22).

This basic teleological or goal-directed orientation of Aristotle’s biology allows him to explain the various functions of living creatures in terms of their growth and preservation of form. Perhaps foremost among these is reproduction, which establishes the continuity of a species through a generation. As Aristotle puts it, the seed is temporally prior to the fully developed organism, since each organism develops from a seed. But the fully developed organism is logically prior to the seed, since it is the end or final cause, for the sake of which the seed is produced (PA 641b29–642a2).

In asexual reproduction in plants and animals, the seed is produced by an individual organism and implanted in soil, which activates it and thus actualizes its potentiality to become an organism of the kind from which it was produced. Aristotle thus utilizes a conception of “type” as an endogenous teleonomic principle, which explains why an individual animal can produce other animals of its own type (Mayr 1982, 88). Hence, the natural kind to which an individual belongs makes it what it is. Animals of the same natural kind have the same form of life and can reproduce with one another but not with animals of other kinds.

In animal sexual reproduction, Aristotle understands the seed possessed by the male as the source or principle of generation, which contains the form of the animal and must be implanted in the female, who provides the matter (GA 716a14–25). In providing the form, the male sets up the formation of the embryo in the matter provided by the female, as rennet causes milk to coagulate into cheese (GA 729a10–14). Just as rennet causes milk to separate into a solid, earthy part (or cheese), and a fluid, watery part (or whey), so the semen causes the menstrual fluid to set. In this process, the principle of growth potentially contained in the seed is activated, which, like a seed planted in soil, produces an animal’s body as the embryo (GA 739b21–740a9).

The form of the animal, its psyche, may thus be said to be potentially in the matter, since the matter contains all the necessary nutrients for the production of the complete organism. However, it is invariably the male that brings about the reproduction by providing the principle of the perceptual soul, a process Aristotle compares with the movement of automatic puppets by a mover that is not in the puppet (GA 741b6–15). (Whether the female produces the nutritive psyche is an open question.) Thus, form or psyche is provided by the male, while the matter is provided by the female: when the two come together, they form a hylomorphic product—the living animal.

While the form of an animal is preserved in kind by reproduction, organisms are also preserved individually over their natural lifespans through feeding. In species that have blood, feeding is a kind of concoction, in which food is chewed and broken down in the stomach, then enters the blood, and is finally cooked up to form the external parts of the body. In plants, feeding occurs by the nutritive psyche alone. But in animals, the senses exist for the sake of detecting food, since it is by the senses that animals pursue what is beneficial and avoid what is harmful. In human beings, a similar explanation can be given of the intellectual powers: understanding and practical wisdom exist so that human beings might not only live but also enjoy the good life achievable by action (Sens.436b19–437a3).

Although Aristotle’s teleology has been criticized by some modern biologists, others have argued that his biological work is still of interest to naturalists. For example, Haldane (1955) shows that Aristotle gave the earliest report of the bee waggle dance, which received a comprehensive explanation only in the 20th century work of Von Frisch. Aristotle also observed lordosis behavior in cattle (HA 572b1–2) and notes that some plants and animals are divisible (Youth and Old Age 468b2–15), a fact that has been vividly illustrated in modern studies of planaria. Even when Aristotle’s biological explanations are incorrect, his observations may be of enduring value.

iii. Psychology

Psychology is the study of the psyche, which is often translated as “soul.” While prior philosophers were interested in the psyche as a part of political inquiry, for Aristotle, the study of the psyche is part of natural science (Ibn Bajjah 1961, 24), continuous with biology. This is because Aristotle conceives of the psyche as the form of a living being, the body being its material. Although the psyche and body are never really separated, they can be given different descriptions. For example, the passion of anger can be described physiologically as a boiling of the blood around the heart, while it can be described dialectically as the desire to pay back with pain someone who has insulted one (DA 403a25–b2). While the physiologist examines the material and efficient causes, the dialectician considers only the form and definition of the object of investigation (DA 403a30–b3). Since the psyche is “the first principle of the living thing” (DA 402a6–7), neither the dialectical method nor the physiological method nor a combination of the two is sufficient for a systematic account of the psyche (DA 403a2, b8). Rather than relying on dialectical or materialist speculation, Aristotle holds that demonstration is the proper method of psychology, since the starting point is a definition (DA 402b25–26), and the psyche is the form and definition of a living thing.

Aristotle conceives of psychology as an exact science, with greater precision than the lesser sciences (DA 402a1–5), and accordingly offers a complete sequence of the kinds or “parts” of psyche. The nutritive psyche—possessed by both plants and animals—is responsible for the basic functions of nourishment and reproduction. Perception is possible only in an animal that also has the nutritive power that allows it to grow and reproduce, while desire depends on perceiving the object desired, and locomotion depends on desiring objects in different locations (DA 415a1–8). More intellectual powers like imagination, judgment, and understanding itself exist only in humans, who also have the lower powers.

The succession of psychological powers ensures the completeness, order, and necessity of the relations of psychological parts. Like rectilinear figures, which proceed from triangles to quadrilaterals, to pentagons, and so forth, without there being any intermediate forms, there are no other psyches than those in this succession (DA 414b20–32). This demonstrative approach ensures that although the methods of psychology and physiology are distinct, psychological divisions map onto biological distinctions. For Aristotle, the parts of the psyche are not separable or “modular” but related genetically: each posterior part of the psyche “contains” the parts before it, and each lower part is the necessary but not sufficient condition for possession of the part that comes after it.

The psyche is defined by Aristotle as the first actuality of a living animal, which is the form of a natural body potentially having life (DA 412a19–22). This form is possessed even when it is not being used; for example, a sleeping person has the power to hear a melody, though while he is sleeping, he is not exercising the power. In distinction, though a corpse looks just like a sleeping body, it has no psyche, since it lacks the power to respond to such stimuli. The second actuality of an animal comes when the power is actually exercised such as when one actually hears the melody (DA 417b9–16).

Perception is the reception of the form of an object of perception without its matter, just as wax receives the seal of a ring without its iron or gold (DA 424a17–28). When one sees wine, for example, one perceives something dark and liquid without becoming dark and liquid. Some hold that Aristotle thinks the reception of the form happens in matter so that part of the body becomes like the object perceived (for example, one’s eye might be dark while one is looking at wine). Others hold that Aristotelian perception is a spiritual change so that no bodily change is required. But presumably one is changing both bodily and spiritually all the time, even when one is not perceiving. Consequently, the formulation that perception is of “form without matter” is probably not intended to describe physiological or spiritual change but rather to indicate the conceptual nature of perception. For, as discussed in the section on first philosophy below, Aristotle considers forms to be definitions or concepts; for example, one defines “horse” by articulating its form. If he is using “form” in the same way in his discussion of perception, he means that in perceiving something, such as in seeing a horse, one gains an awareness of it as it is; that is, one grasps the concept of the horse. In that case, all the doctrine means is that perception is conceptual, giving one a grasp not just of parts of perceptible objects, say, the color and shape of a horse, but of the objects themselves, that is, of the horse as horse. Indeed, Aristotle describes perception as conferring knowledge of particulars and in that sense being like contemplation (DA 417b19–24).

This theory of perception distinguishes three kinds of perceptible objects: proper sensibles, which are perceived only by one sense modality; common sensibles, which are perceived by all the senses; and accidental sensibles, which are facts about the sensible object that are not directly given (DA 418a8–23). For example, in seeing wine, its color is a proper sensible, its volume a common sensible, and the fact that it belongs to Callias an accidental sensible. While one normally could not be wrong about the wine’s color, one might overestimate or underestimate its volume under nonstandard conditions, and one is apt to be completely wrong about the accidental sensible (for example, Callias might have sold the wine).

The five senses are distinguished by their proper sensibles: though the wine’s color might accidentally make one aware that it is sweet, color is proper to sight and sweetness to taste. But this raises a question: how do the different senses work together to give one a coherent experience of reality? If they were not coordinated, then one would perceive each quality of an object separately, for example, darkness and sweetness without putting them together. However, actual perceptual experience is coordinated: one perceives wine as both dark and sweet. In order to explain this, Aristotle says that they must be coordinated by the central sense, which is probably located in the body’s central organ, the heart. When one is awake, and the external sense organs are functioning normally, they are coordinated in the heart to discern reality as being the way it is (Sens.448b31–449a22).

Aristotle claims that one hears that one hears and sees that one sees (DA 425b12–17). Though there is a puzzle as to whether such higher-order seeing is due to sight itself or to the central perceptual power (compare On Sleep 455a3–26), the higher-order perception counts as an awareness of how the perceptual power grasps an object in the world. Though later philosophers named this higher-order perception “consciousness” and argued that it could be separated from an actualized perception of a real object, for Aristotle it is intrinsically dependent on the first-order grasp of an object (Nakahata 2014, 109–110). Indeed, Aristotle describes perceptual powers as being potentially like the perceptual object in actuality (DA 418a3–5) and goes so far as to say that the activity of the external object and that of the perceptual power are one, though what it is to be each one is different (DA 425b26–27). Thus, consciousness seems to be a property that arises automatically when perception is activated.

In at least some animals, the perceptual powers give rise to other psychological powers that are not themselves perceptual in a strict sense. In one simple case, the perception of a color is altered by its surroundings, that is, by how it is illuminated and by the other colors in one’s field of vision. Far from assuming the constancy of perception, Aristotle notes that under such circumstances, one color can take the place of another and appear differently than it does under standard conditions, for example, of full illumination (Meteor.375a22–28).

Memory is another power that arises through the collection of many perceptions. Memory is an affection of perception (though when the content of the memory is intellectual, it is an affection of the judgmental power of the psyche, see Mem.449b24–25), produced when the motion of perception acts like a signet ring in sealing wax, impressing itself on an animal and leaving an image in the psyche (Mem.450a25–b1). The resultant image has a depictive function so that it can be present even when the object it portrays is absent: when one remembers a person, for example, the memory-image is fully present in one’s psyche, though the person might be absent (Mem.450b20–25).

Closely related to memory, the imagination is a power to present absent things to oneself. Identical neither to perception nor judgment (DA 427b27–8, 433a10), imagining has an “as if” quality. For example, imagining a terror is like looking at a picture without feeling the corresponding emotion of fear (DA 427b21–24). Imagination may be defined as a kind of change or motion that comes about by means of activated perception (DA 429a1–2). This does not entail that imagination is merely reproductive but simply that activated perceptions trigger the imagination, which in turn produces an image or appearance “before our eyes” (DA 427b19–20). The resultant appearances that “comes to be for us” (DA 428a1–2, 11–12) could be true or false, since unlike the object of perception, what is imagined is not present (Humphreys 2019).

Human beings are distinct from other animals, Aristotle says, in their possession of rational psyche. Foremost among the rational powers is intellect or understanding (this article uses the terms interchangeably), which grasps universals in a way that is analogous to the perceptual grasp of particulars. However, unlike material particulars grasped by perception, universals are not mixed with body and are thus in a sense contained in the psyche itself (DA 417b22–24, 432a1–3). This has sometimes been called the intentional inexistence of an object, or intentionality, the property of being directed to or about something. Since one can think or understand any universal, the understanding is potentially about anything, like an empty writing tablet (DA 429b29–430a1).

The doctrine of the intentionality of intellect leads Aristotle to make a distinction between two kinds of intellect. Receptive or passive intellect is characterized by the ability to become like all things and is analogous to the writing tablet. Productive or active intellect is characterized by the ability to bring about all things and is analogous to the act of writing. The active intellect is thus akin to the light that illuminates objects, making them perceptible by sight. Aristotle holds that the soul never thinks without an image produced by imagination to serve as its material. Thus, in understanding something, the productive intellect actuates the receptive intellect, which stimulates the imagination to produce a particular image corresponding to the universal content of the understanding. Hence, while Aristotle describes the active intellect as unaffected, separate, and immaterial, it serves to bring to completion the passive intellect, the latter of which is inseparable from imagination and hence from perception and nutrition.

Aristotle’s insistence that intellect is not a subject of natural science (PA 641a33–b9) motivates the view that thinking requires a contribution from the supernatural or divine. Indeed, in Metaphysics (1072b19–30) Aristotle argues that intellect actively understanding the intelligible is the everlasting God. For readers like the medieval Arabic commentator Ibn Rushd, passive intellect is spread like matter among thinking beings. This “material intellect” is activated by God, the agent intellect, so that when one is thinking, one participates in the activity of the divine intellect. According to this view, every act of thinking is also an act of divine illumination in which God actuates one’s thinking power as the writer actuates a blank writing tablet.

However, in other passages Aristotle says that when the body is destroyed, the soul is destroyed too (Length and Shortness of Life, 465b23–32). Thus, it seems that Aristotle’s psychological explanations assume embodiment and require that thinking be something done by the individual human being. Indeed, Aristotle argues that if thinking is either a kind of imaginative representation or impossible without imagination, then it will be impossible without body (DA 403a8–10). But the psyche never thinks without imagination (DA 431a16–17). It seems to follow that far from being a part of the everlasting thinking of God, human thinking is something that happens in a living body and ends when that body is no longer alive. Thus, Jiminez (2014, 95–99) argues that thinking is embodied in three ways: it is proceeded by bodily processes, simultaneous with embodied processes, and anticipates bodily processes, namely intentional actions. For further discussion see Jiminez (2017).

The whole psyche governs the characteristic functions and changes of a living thing. The nutritive psyche is the formal cause of growth and metabolism and is shared by plants, while the perceptual psyche gives rise to desire, which causes self-moving animals to act. When one becomes aware of an apparent good by perception or imagination, one forms either an appetite, the desire for pleasure, or thumos, the spirited desire for revenge or honor. A third form of desire, wish, is the product of the rational psyche (DA 433a20–30).

Boeri has pointed out that Aristotle’s psychology cuts a middle path between physicalism, which identifies the psyche with body, and dualism, which posits the independent existence of the soul and body. By characterizing the psyche as he does, Aristotle can at once deny that the psyche is a body but also insist that it does not exist without a body. The living body of an animal can thus be thought of as a form that has been “materialized” (Boeri 2018, 166–169).

b. Mathematics

Aristotle was educated in Plato’s Academy, in which it was commonly argued that mathematical objects like lines and numbers exist independently of physical beings and are thus ”separable” from matter. Aristotle’s conception of the hierarchy of beings led him to reject Platonism since the category of quantity is posterior to that of substance. But he also rejects nominalism, the view that mathematical things are not real. Against both positions, Aristotle argues that mathematical things are real but do not exist separately from sensible bodies (Met.1090a29–30, 1093b27–28). Mathematical objects thus depend on the things in which they inhere and have no separate or independent being (Met.1059b12–14).

Although mathematical beings are not separate from the material cosmos, when the mathematician defines what it is to be a sphere or circle, he does not include a material like gold or bronze in the definition, because it is not the gold ball or bronze ring that the mathematician wants to define. The mathematician is justified in proceeding in this way, because although there are no separate entities beyond the concrete thing, it is just the mathematical aspects of real things that are relevant to mathematics (DC 278a2–6). This process by which the material features of a substance are systematically ignored by the mathematician, who focuses only on the quantitative features, Aristotle describes as “abstraction.” Because it always involves final ends, no abstraction is possible in natural science (PA 641b11–13, Phys.193b31–35). A consequence of this abstraction is that “why” questions in mathematics are invariably answered not by providing a final cause but by giving the correct definition (Phys.198a14–21, 200a30–34).

One reason that Aristotle believes that mathematics must proceed by abstraction is that he wants to prevent a multiplication of entities. For example, he does not want to say that, in addition to there being a sphere of bronze, there is another separate, mathematical sphere, and that in addition to that sphere, there is a separate mathematical plane cutting it, and that in addition to that plane, there is an additional line limiting the plane (see Katz 2014). It is enough for a mathematical ontology simply to acknowledge that natural objects have real mathematical properties not separate in being, which can nevertheless be studied independently from natural investigation. Aristotle also favors this view due to his belief that mathematics is a demonstrative science. Aristotle was aware that geometry uses diagrammatic representations of abstracted properties, which allow one to grasp how a demonstration is true not just of a particular object but of any class of objects that share its quantitative features (Humphreys 2017). Through the concept of abstraction, Aristotle could explain why a particular diagram may be used to prove a universal geometrical result.

Why study mathematics? Although Aristotle rejected the Platonic doctrine that mathematical beings are separate, intermediate entities between perceptible things and forms, he agreed with the Platonists that mathematics is about things that are beautiful and good, since it offers insight into the nature of arrangement, symmetry, and definiteness (Met.1078a31–b6). Thus, the study of mathematics reveals that beauty is not so much in the eye of the beholder as it is in the nature of things (Hoinski and Polansky 2016, 51–60). Moreover, Aristotle holds that mathematical beings are all potential objects of the intellect, which exist only potentially when they are not understood. The activity of understanding is the actuation of their being, but also actuates the intellect (Met.1051a26–33). Mathematics, then, not only gives insight into beauty but is also a source of intellectual pleasure, since gaining mathematical knowledge exercises the human being’s best power.

c. First Philosophy

In addition to natural and mathematical sciences, there is a science of independent beings that Aristotle calls “first philosophy” or “wisdom.” What is the proper aim of this science? In some instances, Aristotle seems to say that it concerns being insofar as it is (Met.1003a21–22), whereas in others, he seems to consider it to be equivalent to “theology,” restricting contemplation to the highest kind of being (Met.1026a19–22), which is unchanging and separable from matter. However, Menn (2013, 10–11) shows that Aristotle is primarily concerned with describing first philosophy as a science that seeks the causes and sources of being qua being. Hence, when Aristotle holds that wisdom is a kind of rational knowledge concerning causes and principles (Met.982a1–3), he probably means that the investigation of these causes of being as being seeks to discover the divine things as the cause of ordinary beings. First philosophy is consequently quite unlike natural philosophy and mathematics, since rather than proceeding from systematic observation or from hypotheses, it begins with an attitude of wonder towards ordinary things and aims to contemplate them not under a particular description but simply as beings (Sachs 2018).

The fundamental premise of this science is the law of noncontradiction, which states that something cannot both be and not be (Met.1006a1). Aristotle holds that this law is indemonstrable and necessary to assume in any meaningful discussion about being. Consequently, a person who demands a demonstration of this principle is no better than a plant. As Anscombe (1961, 40) puts it, “Aristotle evidently had some very irritating people to argue with.” But as Anscombe also points out, this principle is what allows Aristotle to make a distinction between substances as the primary kind of being and accidents that fall in the other categories. While it is possible for a substance to take on contrary accidents, for example, coffee first being hot and later cold, substances have no contraries. The law requires that a substance either is or is not, independently of its further, accidental properties.

Aristotle insists that in order for the word “being” to have any meaning at all, there must be some primary beings, whereas other beings modify these primary beings (Met.1003b6–10). As we saw in the section on Aristotle’s logic, primary substances are individual substances while their accidents are what is predicated of them in the categories. This takes on metaphysical significance when one thinks of this distinction in terms of a dependence relation in which substances can exist independently of their accidents, but accidents are dependent in being on a substance. For example, a shaggy dog is substantially a dog, but only accidentally shaggy. If it lost all its hair, it would cease to be shaggy but would be no less a dog: it would then be a non-shaggy dog. But if it ceased to be a dog—for example, if it were turned into fertilizer—then it would cease to be shaggy at the same moment. Unlike the “shagginess,” “dogness” cannot be separated from a shaggy dog: the “what it is to be” a dog is the dog’s dogness in the category of substance, while its accidents are in other categories, in this case shagginess being in the category of quality (Met.1031a1–5).

Given that substances can be characterized as forms, as matter, or as compounds of form and matter, it seems that Aristotle gives the cause and source of a being by listing its material and formal cause. Indeed, Aristotle sometimes describes primary being as the “immanent form” from which the concrete primary being is derived (Met.1037a29). This probably means that a primary substance is always a compound, its formal component serving as the substance’s final cause. However, primary beings are not composed of other primary beings (Met.1041a3–5). Thus, despite some controversy on the question, there seems to be no form of an individual, form being what is shared by all the individuals of a kind.

A substance is defined by a universal, and thus when one defines the form, one defines the substance (Met.1035b31–1036a1). However, when one grasps a substance directly in perception or thought, one grasps the compound of form and matter (Met.1036a2–8). But since form by itself does not make a primary substance, it must be immanent—that is, compounded with matter—in each individual, primary substance. Rather, in a form-matter compound, such as a living thing, the matter is both the prior stuff out of which the thing has become and the contemporaneous stuff of which it is composed. The form is what makes what a thing is made of, its matter, into that thing (Anscombe 1961, 49, 53).

Due to this hylomorphic account, one might worry that natural science seems to explain everything there is to explain about substances. However, Aristotle insists that there is a kind of separable and immovable being that serves as the principle or source of all other beings, which is the special object of wisdom (Met.1064a35–b1). This being might be called the good itself, which is implicitly pursued by substances when they come to be what they are. In any case, Aristotle insists that this source and first of beings sets in motion the primary motion. But since whatever is in motion must be moved by something else, and the first thing is not moved by something else, it is itself motionless (Met.1073a25–34). As we have seen, even the human intellect is “not affected” (DA 429b19–430a9), producing its own object of contemplation in a pure activity. Following this, Aristotle describes the primary being as an intellect or a kind of intellect that “thinks itself” perpetually (Met.1072b19–20). Thus, we can conceive of the Aristotelian god as being like our own intellect but unclouded by what we undergo as mortal, changing, and fallible beings (Marx 1977, 7–8).

4. Practical Philosophy

Practical philosophy is distinguished from theoretical philosophy both in its goals and in its methods. While the aim of theoretical philosophy is contemplation and the understanding of the highest things, the aim of practical philosophy is good action, that is, acting in a way that constitutes or contributes to the good life. But human beings can only thrive in a political community: the human is a “political animal” and thus the political community exists by nature (Pol.1253a2–5, compare EN 1169b16–19). Thus, ethical inquiry is part of political inquiry into what makes the best life for a human being. Because of the intrinsic variability and complexity of human life, however, this inquiry does not possess the exactness of theoretical philosophy (EN 1094b10–27).