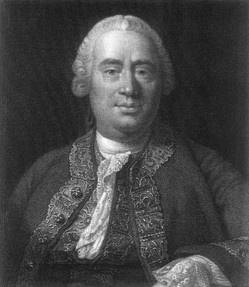

David Hume: Moral Philosophy

Although David Hume (1711-1776) is commonly known for his philosophical skepticism, and empiricist theory of knowledge, he also made many important contributions to moral philosophy. Hume’s ethical thought grapples with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, human sociability, and what it means to live a virtuous life. As a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, Hume’s ethical thought variously influenced, was influenced by, and faced criticism from, thinkers such as Shaftesbury (1671-1713), Francis Hutcheson (1694-1745), Adam Smith (1723-1790), and Thomas Reid (1710-1796). Hume’s ethical theory continues to be relevant for contemporary philosophers and psychologists interested in topics such as metaethics, the role of sympathy and empathy within moral evaluation and moral psychology, as well as virtue ethics.

Although David Hume (1711-1776) is commonly known for his philosophical skepticism, and empiricist theory of knowledge, he also made many important contributions to moral philosophy. Hume’s ethical thought grapples with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, human sociability, and what it means to live a virtuous life. As a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, Hume’s ethical thought variously influenced, was influenced by, and faced criticism from, thinkers such as Shaftesbury (1671-1713), Francis Hutcheson (1694-1745), Adam Smith (1723-1790), and Thomas Reid (1710-1796). Hume’s ethical theory continues to be relevant for contemporary philosophers and psychologists interested in topics such as metaethics, the role of sympathy and empathy within moral evaluation and moral psychology, as well as virtue ethics.

Hume’s moral thought carves out numerous distinctive philosophical positions. He rejects the rationalist conception of morality whereby humans make moral evaluations, and understand right and wrong, through reason alone. In place of the rationalist view, Hume contends that moral evaluations depend significantly on sentiment or feeling. Specifically, it is because we have the requisite emotional capacities, in addition to our faculty of reason, that we can determine that some action is ethically wrong, or a person has a virtuous moral character. As such, Hume sees moral evaluations, like our evaluations of aesthetic beauty, as arising from the human faculty of taste. Furthermore, this process of moral evaluation relies significantly upon the human capacity for sympathy, or our ability to partake of the feelings, beliefs, and emotions of other people. Thus, for Hume there is a strong connection between morality and human sociability.

Hume’s philosophy is also known for a novel distinction between natural and artificial virtue. Regarding the latter, we find a sophisticated account of justice in which the rules that govern property, promising, and allegiance to government arise through complex processes of social interaction. Hume’s account of the natural virtues, such as kindness, benevolence, pride, and courage, is explained with rhetorically gripping and vivid illustrations. The picture of human excellence that Hume paints for the reader equally recognizes the human tendency to praise the qualities of the good friend and those of the inspiring leader. Finally, the overall orientation of Hume’s moral philosophy is naturalistic. Instead of basing morality on religious and divine sources of authority, Hume seeks an empirical theory of morality grounded on observation of human nature.

Hume’s moral philosophy is found primarily in Book 3 of The Treatise of Human Nature and his Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, although further context and explanation of certain concepts discussed in those works can also be found in his Essays Moral, Political, and Literary. This article discusses each of the topics outlined above, with special attention given to the arguments he develops in the Treatise.

Table of Contents

- Hume’s Rejection of Moral Rationalism

- Hume’s Moral Sense Theory

- Sympathy and Humanity

- Hume’s Classification of the Virtues and the Standard of Virtue

- Justice and the Artificial Virtues

- The Natural Virtues

- References and Further Reading

1. Hume’s Rejection of Moral Rationalism

Many philosophers have believed that the ability to reason marks a strict separation between humans and the rest of the natural world. Views of this sort can be found in thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes, and Kant. One of the more philosophically radical aspects of Hume’s thought is his attack on this traditional conception. For example, he argues that the same evidence we have for thinking that human beings possess reason should also lead us to conclude that animals are rational (T 1.3.16, EHU 9). Hume also contends that the intellect, or “reason alone,” is relatively powerless on its own and needs the assistance of the emotions or “passions” to be effective. This conception of reason and emotion plays a critical role in Hume’s moral philosophy.

One of the foremost topics debated in the seventeenth and eighteenth century about the nature of morality was the relationship between reason and moral evaluation. Hume rejected a position known as moral rationalism. The moral rationalists held that ethical evaluations are made solely upon the basis of reason without the influence of the passions or feelings. The seventeenth and eighteenth century moral rationalists include Ralph Cudworth (1617-1688), Samuel Clarke (1675-1729), and John Balguy (1688-1748). Clarke, for instance, writes that morality consists in certain “necessary and eternal” relations (Clarke 1991[1706]: 192). He argues that it is “fit and reasonable in itself” that one should preserve the life of an innocent person and, likewise, unfit and unreasonable to take someone’s life without justification (Clarke 1991[1706]: 194). The very relationship between myself, a rational human being, and this other individual, another rational human being who is innocent of any wrongdoing, implies that it would be wrong of me to kill this person. The moral truths implied by such relations are just as evident as the truths implied by mathematical relations. It is just as irrational to (a) deny the wrongness of killing an innocent person as it would be to (b) deny that three multiplied by three is equal to nine (Clarke 1991[1706]: 194). As evidence, Clarke points out that both (a) and (b) enjoy nearly universal agreement. Thus, Clarke believes we should conclude that both (a) and (b) are self-evident propositions discoverable by reason alone. Consequently, it is in virtue of the human ability to reason that we make moral evaluations and recognize our moral duties.

a. The Influence Argument

Although Hume rejects the rationalist position, Hume does allow that reason has some role to play in moral evaluation. In the second Enquiry Hume argues that, although our determinations of virtue and vice are based upon an “internal sense or feeling,” reason is needed to ascertain the facts required to form an accurate view of the person being evaluated and, thus, is necessary for accurate moral evaluations (EPM 1.9). Hume’s claim, then, is more specific. He denies that moral evaluation is the product of “reason alone.” It is not solely because of the rational part of human nature that we can distinguish moral goodness from moral badness. Not “every rational being” can make moral evaluations (T 3.1.1.4). Purely rational beings that are devoid of feelings and emotion, if any such beings exist, could not understand the difference between virtue and vice. Something other than reason is required. Below is an outline of the argument Hume gives for this conclusion at T 3.1.1.16. Call this the “Influence Argument.”

- Moral distinctions can influence human actions.

- “Reason alone” cannot influence human actions.

- Therefore, moral distinctions are not the product of “reason alone.”

Let us begin by considering premise (1). Notice that premise (1) uses the term “moral distinctions.” By “moral distinction” Hume means evaluations that differentiate actions or character traits in terms of their moral qualities (T 3.1.1.3). Unlike the distinctions we make with our pure reasoning faculty, Hume claims moral distinctions can influence how we act. The claim that some action, X, is vicious can make us less likely to perform X, and the opposite in the case of virtue. Those who believe it is morally wrong to kill innocent people will, consequently, be less likely to kill innocent people. This does not mean moral evaluations motivate decisively. One might recognize that X is a moral duty, but still fail to do X for various reasons. Hume only claims that the recognition of moral right and wrong can motivate action. If moral distinctions were not practical in this sense, then it would be pointless to attempt to influence human behavior with moral rules (T 3.1.1.5).

Premise (2) requires a more extensive justification. Hume provides two separate arguments in support of (2), which have been termed by Rachel Cohon as the “Divide and Conquer Argument” and the “Representation Argument” (Cohon 2008). These arguments are discussed below.

b. The Divide and Conquer Argument

Hume reminds us that the justification for premise (2) of the Influence Argument was already established earlier at Treatise 2.3.3 in a section entitled “Of the influencing motives of the will.” Hume begins this section by observing that many believe humans act well by resisting the influence of our passions and following the demands of reason (T 2.3.3.1). For instance, in the Republic Plato (427–347 B.C.E.) outlines a conception of the well-ordered soul in which the rational part rules over the soul’s spirited and appetitive parts. Or, consider someone who knows that eating another piece of cake is harmful to her health, and values her health, but still eats another piece of cake. Such situations are often characterized as letting passion or emotion defeat reason. Below is the argument that Hume uses to reject this conception.

- Reason is either demonstrative or probable.

- Demonstrative reason alone cannot influence the will (or influence human action).

- Probable reason alone cannot influence the will (or influence human action).

- Therefore, “reason alone” cannot influence the will (or influence human action).

This argument is referred to as the “Divide and Conquer Argument” because Hume divides reasoning into two types, and then demonstrates that neither type of reasoning can influence the human will by itself. From this, it follows that “reason alone” cannot influence the will.

The first type of reasoning Hume discusses is demonstrative reasoning that involves “abstract relations of ideas” (T 2.3.3.2). Consider demonstratively certain judgments such as “2+2=4” or “the interior angles of a triangle equal 180 degrees.” This type of reason cannot motivate action because our will is only influenced by what we believe has physical existence. Demonstrative reason, however, only acquaints us with abstract concepts (T 2.3.3.2). Using Hume’s example, mathematical demonstrations might provide a merchant with information about how much money she owes to another person. Yet, this information only matters because she has a desire to square her debt (T 2.3.3.2). It is this desire, not the demonstrative reasoning itself, which provides the motivational force.

Why can probable reasoning not have practical influence? Probable reasoning involves making inferences on the basis of experience (T 2.3.3.1). An example of this is the judgments we make of cause and effect. As Hume established earlier in the Treatise, our judgments of cause and effect involve recognizing the “constant conjunction” of certain objects as revealed through experience (see, for instance, T 1.3.6.15). Since probable reasoning can inform us of what actions have a “constant conjunction” with pleasure or pain, it might seem that probable reasoning could influence the will. However, the fundamental motivational force does not arise from our ability to infer the relation of cause and effect. Rather, the source of our motivation is the “impulse” to pursue pleasure and avoid pain. Thus, once again, reason simply plays the role of discovering how to satisfy our desires (T 2.3.3.3). For example, my belief that eating a certain fruit will cause good health seems capable of motivating me to eat that fruit (T 3.3.1.2). However, Hume argues that this causal belief must be accompanied with some passion, specifically the desire for good health, for it to move the will. We would not care about the fact that eating the fruit contributes to our health if health was not a desired goal. Thus, Hume sketches a picture in which the motivational force to pursue a goal always comes from passion, and reason merely informs us of the best means for achieving that goal (T 2.3.3.3).

Consequently, when we say that some passion is “unreasonable,” we mean either that the passion is founded upon a false belief or that passion impelled us to choose the wrong method for achieving our desired end (T 2.3.3.7). In this context Hume famously states that it is “not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger” (T 2.3.3.6). It can be easy to misunderstand Hume’s point here. Hume does not believe there is no basis for condemning the person who prioritizes scratching her finger. Hume’s point is simply that reason itself cannot distinguish between these choices. A being that felt completely indifferent toward both the suffering and well-being of other human beings would have no preference for what outcome results (EPM 6.4).

The second part of Hume’s thesis is that, because “reason alone” cannot motivate actions, there is no real conflict between reason and passion (T 2.3.3.1). The view that reason and passion can conflict misunderstands how each functions. Reason can only serve the ends determined by our passions. As Hume explains in another well-known quote “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions” (T 2.3.3.4). Reason and passion have fundamentally different functions and, thus, cannot encroach upon one another. Why do we commonly describe succumbing to temptation as a failure to follow reason? Hume explains that the operations of the passions and reason often feel similar. Specifically, both the calm passions that direct us toward our long-term interest, as well as the operations of reason, exert themselves calmly (T 2.3.3.8). Thus, the person who possesses “strength of mind,” or what is commonly called “will power,” is not the individual whose reason conquers her passions. Instead, being strong-willed means having a will that is primarily influenced by calm instead of violent passions (T 2.3.3.10).

c. The Representation Argument

The second argument in support of premise (2) of the “Influence Argument” is found in both T 3.3.1 and T 2.3.3. This argument is commonly referred to as the “Representation Argument.” It is expressed most succinctly at T 3.3.1.9. The argument has two parts. The first part of the argument is outlined below.

- That which is an object of reason must be capable of being evaluated as true or false (or be “truth-apt”).

- That which is capable of being evaluated as true or false (or is “truth-apt”) must be capable of agreement (or disagreement) with some relation of ideas or matter of fact.

- Therefore, that which can neither agree (nor disagree) with any relation of ideas or matter of fact cannot be an object of reason.

The first portion of the argument establishes what reason can (and cannot) accomplish. Premise (1) relies on the idea that the purpose of reason is to discover truth and falsehood. In fact, in an earlier Treatise section Hume describes truth as the “natural effect” of our reason (T 1.4.1.1). So, whatever is investigated or revealed through reason must be the sort of claim that it makes sense to evaluate as true or false. Philosophers call such claims “truth-apt.” What sorts of claims are truth-apt? Only those claims which can agree (or disagree) with some abstract relation of ideas or fact about existence. For instance, the claim that “the interior angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees” agrees with the relation of ideas that makes up our concept of triangle. Thus, such a claim is true. The claim that “China is the most populated country on planet Earth” agrees with the empirical facts about world population and, thus, can also be described as true. Likewise, the claims that “the interior angles of a triangle add up to 200 degrees” or that “the United States is the most populated country on planet Earth” do not agree with the relevant ideas or existential facts. Yet, because it is appropriate to label each of these as false, both claims are still “truth-apt.” From this, it follows that something can only be an object of reason if it can agree or disagree with a relation of ideas or matter of fact.

Is that which motivates our actions “truth-apt” and, consequently, within the purview of reason? Hume addresses that point in the second part of the Representation Argument:

4. Human “passions, volitions, and actions” (PVAs) can neither agree (nor disagree) with any relation of ideas or matter of fact.

5. Therefore, PVAs cannot be objects of reason (or reason cannot produce action).

Why does the argument talk about “passions, volitions, and actions” (PVAs) in premise (4)? PVAs are the component parts of motivation. Passions cause desire or aversion toward a certain object, which results in the willing of certain actions. Thus, the argument hinges on premise (4)’s claim that PVAs can never agree or disagree with relations of ideas or matters of fact. Hume’s justification for this claim is again found at T 2.3.3.5 from the earlier Treatise section “Of the Influencing Motives of the Will.” Here Hume argues that for something to be truth-apt it must have a “representative quality” (T 2.3.3.5). That is, it must represent some type of external reality. The claim that “the interior angles of a triangle equal 180 degrees” represents a fact about our concept of a triangle. The claim that “China is the most populated country on planet Earth” represents a fact about the current population distribution of Earth. Hume argues the same cannot be said of passions such as anger. The feeling of anger, just like the feeling of being thirsty or being ill, is not meant to be a representation of some external object (T 2.3.3.5). Anger, of course, is a response to something external. For example, one might feel anger in response to a friend’s betrayal. However, this feeling of anger is not meant to represent my friend’s betrayal. A passion or emotion is simply a fact about the person who feels it. Consequently, since reason only deals with what is truth-apt, it follows that (5) PVAs cannot be objects of reason.

d. Hume and Contemporary Metaethics

Hume’s moral philosophy has continued to influence contemporary philosophical debates in metaethics. Consider the following three metaethical debates.

Moral Realism and Anti-Realism: Moral realism holds that moral statements, such as “lying is morally wrong,” describe mind-independent facts about the world. Moral anti-realism denies that moral statements describe mind-independent facts about the world.

Moral Cognitivism and Noncognitivism: Moral cognitivism holds that moral statements, such as “lying is morally wrong,” are capable of being evaluated as true or false (or are “truth-apt”). Moral noncognitivism denies that such statements can be evaluated as true or false (or can be “truth-apt”).

Moral Internalism and Externalism: Moral internalism holds that someone who recognizes that it is one’s moral obligation to perform X necessarily has at least some motive to perform X. Moral externalism holds that one can recognize that it is one’s moral obligation to perform X and simultaneously not have any motive to perform X.

While there is not just one “Humean” position on each of these debates, many contemporary meta-ethicists who see Hume as a precursor take a position that combines anti-realism, noncognitivism, and internalism. Much of the support for reading Hume as an anti-realist comes from consideration of his moral sense theory (which is examined in the next section). Evidence for an anti-realist reading of Hume is often found at T 3.1.1.26. Hume claims that, for any vicious action, the moral wrongness of the action “entirely escapes you, as long as you consider the object.” Instead, to encounter the moral wrongness you must “turn your reflexion into your own breast” (T 3.1.1.26). The wrongness of murder, taking Hume’s example, does not lie in the act itself as something that exists apart from the human mind. Rather, the wrongness of murder lies in how the observer reacts to the murder or, as we will see below, the painful sentiment that such an act produces in the observer.

The justification for reading Hume as an internalist comes primarily from the Influence Argument, which relies on the internalist idea that moral distinctions can, by themselves, influence the will and produce action. The claim that Hume is a noncognitivist is more controversial. Support for reading Hume as a noncognitivist is sometimes found in the so-called “is-ought” paragraph. There Hume warns us against deriving a conclusion that we “ought, or ought not” do something from the claim that something “is, and is not” the case (T 3.1.1.27). There is significant debate among Hume scholars about what Hume means to say in this passage. According to one interpretation, Hume is denying that it is appropriate to derive moral conclusions (such as “one should give to charity”) from any set of strictly factual or descriptive premises (such as “charity relieves suffering”). This is taken to imply support for noncognitivism by introducing a strict separation between facts (which are truth-apt) and values (which are not truth-apt).

Some have questioned the standard view of Hume as a noncognitivist. Hume does think (as seen in the Representation Argument) that the passions, which influence the will, are not truth-apt. Does the same hold for the moral distinctions themselves? Rachel Cohon has argued, to the contrary, that moral distinctions describe statements that are evaluable as true or false (Cohon 2008). Specifically, they describe beliefs about what character traits produce pleasure and pain in human spectators. If this interpretation is correct, then Hume’s metaethics remains anti-realist (moral distinctions refer to facts about the minds of human observers), but it can also be cognitivist. That is because the claim that human observers feel pleasure in response to some character trait represents an external matter of fact and, thus, can be denominated true or false depending upon whether it represents this matter of fact accurately.

2. Hume’s Moral Sense Theory

Hume claims that if reason is not responsible for our ability to distinguish moral goodness from badness, then there must be some other capacity of human beings that enables us to make moral distinctions (T 3.1.1.4). Like his predecessors Shaftesbury (1671-1713) and Francis Hutcheson (1694-1745), Hume believes that moral distinctions are the product of a moral sense. In this respect, Hume is a moral sentimentalist. It is primarily in virtue of our ability to feel pleasure and pain in response to various traits of character, and not in virtue of our capacity of “reason alone,” that we can distinguish between virtue and vice. This section covers the major elements of Hume’s moral sense theory.

a. The Moral Sense

Moral sense theory holds, roughly, that moral distinctions are recognized through a process analogous to sense perception. Hume explains that virtue is that which causes pleasurable sensations of a specific type in an observer, while vice causes painful sensations of a specific type. While all moral approval is a sort of pleasurable sensation, this does not mean that all pleasurable sensations qualify as instances of moral approval. Just as the pleasure we feel in response to excellent music is different from the pleasure we derive from excellent wine, so the pleasure we derive from viewing a person’s character is different from the pleasure we derive from inanimate objects (T 3.1.2.4). So, moral approval is a specific type of pleasurable sensation, only felt in response to persons, with a particular phenomenological quality.

Along with the common experience of feeling pleasure in response to virtue and pain when confronted with vice (T 3.1.2.2), Hume also thinks this view follows from his rejection of moral rationalism. Everything in the mind, Hume argues, is either an impression or idea. Hume understands an impression to be the first, and most forceful, appearance of a sensation or feeling in the human mind. An idea, by contrast, is a less forceful copy of that initial impression that is preserved in memory (T 1.1.1.1). Hume holds that all reasoning involves comparing our ideas. This means that moral rationalism must hold that we arrive at an understanding of morality merely through a comparison of ideas (T 3.1.1.4). However, since Hume has shown that moral distinctions are not the product of reason alone, moral distinctions cannot be made merely through comparison of ideas. Therefore, if moral distinctions are not made by comparing ideas, they must be based upon our impressions or feelings.

Hume’s claim is not that virtue is an inherent quality of certain characters or actions, and that when we encounter a virtuous character we feel a pleasurable sensation that constitutes evidence of that inherent quality. If that were true, then the moral status of some character trait would be inferred from the fact that we are experiencing a pleasurable sensation. This would conflict with Hume’s anti-rationalism. Hume reiterates this point, stating that spectators “do not infer a character to be virtuous, because it pleases: But in feeling that it pleases [they] in effect feel that it is virtuous” (T 3.1.2.3). Because moral distinctions are not made through a comparison of ideas, Hume believes it is more accurate to say that morality is a matter of feeling rather than judgment (T 3.1.2.1). Since virtue and vice are not inherent properties of actions or persons, what constitutes the virtuousness (or viciousness) of some action or character must be found within the observer or spectator. When, for example, someone determines that some action or character trait is vicious, this just means that your (human) nature is constituted such that you respond to that action or character trait with a feeling of disapproval (T 3.1.1.26). One’s ability to see the act of murder, not merely as a cause of suffering and misery, but as morally wrong, depends upon the emotional capacity to feel a painful sentiment in response to this phenomenon. Thus, Hume claims that the quality of “vice entirely escapes you, as long as you consider the object” (T 3.1.1.26). Virtue and vice exist, in some sense, through the sentimental reactions that human observers toward various “objects.”

This provides the basis for Hume’s comparison between moral evaluation and sense perception, which lies at the foundation of his moral sense theory. Just like the experiences of taste, smell, sight, hearing, and touch produced by our physical senses, virtue and vice exist in the minds of human observers instead of in the actions themselves (T 3.1.1.26). Here Hume appeals to the primary-secondary quality distinction. Sensory qualities and moral qualities are both observer-dependent. Just as there would be no appearance of color if there were no observers, so there would also be no such thing as virtue or vice without beings capable of feeling approval or disapproval in response to human actions. Likewise, a human being who lacked the required emotional capacities would be unable to understand what the rest of us mean when we say that some trait is virtuous or vicious. For instance, imagine a psychopath who has the necessary reasoning ability to understand the consequences of murder, but lacks aversion toward it and, thus, cannot determine or recognize its moral status. In fact, the presence of psychopathy, and the inability of psychopaths to understand moral judgments, is sometimes taken as an objection to moral rationalism.

Furthermore, our moral sense responds specifically to some “mental quality” (T 3.3.1.3) of another person. We can think of a “mental quality” as a disposition one has to act in certain ways or as a character trait. For example, when we approve of the courageous individual, we are approving of that person’s willingness to stand resolute in the face of danger. Consequently, actions can only be considered virtuous derivatively, as signs of another person’s mental dispositions and qualities (T 3.3.1.4). A single action, unlike the habits and dispositions that characterize our character, is fleeting and may not accurately represent our character. Only settled character traits are sufficiently “durable” to determine our evaluations of others (T 3.3.1.5). For this reason, Hume’s ethical theory is sometimes seen as a form of virtue ethics.

b. The General Point of View

Hume posits an additional requirement that some sentiment must meet to qualify as a sentiment of moral approval (or disapproval). Imagine a professor unfairly shows favor toward one student by giving her an “A” for sub-standard work. In this case, it is not difficult to imagine the student being pleased with the professor’s actions. However, if she was honest, that student would likely not think she was giving moral approval of the professor’s unfair grading. Instead, she is evaluating the influence the professor’s actions have upon her perceived self-interest. This case suggests that there is an important difference between the evaluations we make of other people based upon how they influence our interests, and the evaluations we make of others based upon their moral character.

This idea plays a significant role in Hume’s moral theory. Moral approval only occurs from a perspective in which the spectator does not take her self-interest into consideration. Rather, moral approval occurs from a more “general” vantage point (T 3.1.2.4). In the conclusion to the second Enquiry Hume makes this point by distinguishing the languages of morality and self-interest. When someone labels another “his enemy, his rival, his antagonist, his adversary,” he is evaluating from a self-interested point of view. By contrast, when someone labels another with moral terms like “vicious or odious or depraved,” she is inhabiting a general point of view where her self-interest is set aside (EPM 9.6). Speaking the language of morality, then, requires abstracting away from one’s personal perspective and considering the wider effects of the conduct under evaluation. This unbiased point of view is one aspect of what Hume refers to as the “general” (T 3.3.1.15) or “common” (T 3.3.1.30, EPM 9.6) point of view. Furthermore, he suggests that the ability to transcend our personal perspective, and adopt a general vantage point, ties human beings together as “the party of humankind against vice and disorder, its common enemy” (EPM 9.9). Thus, Hume’s theory of moral approval is related in important ways to his larger goal of demonstrating that moral life is an expression of human sociability.

The general vantage point from which moral evaluations are made does not just exclude considerations of self-interest. It also corrects for other factors that can distort our moral evaluations. For instance, adoption of the general point of view corrects our natural tendency to give greater praise to those who exist in close spatial-temporal proximity. Hume notes that someone might feel a stronger degree of praise for her hardworking servant than she feels for the historical representation of Marcus Brutus (T 3.3.1.16). From an objective point of view, Brutus merits greater praise for his moral character. However, we are acquainted with our servant and frequently interact with him. Brutus, on the other hand, is only known to us through historical accounts. Temporal distance causes our immediate, natural feelings of praise for Brutus to be less intense than the approval we give to our servant. Yet, this variation is not reflected in our moral evaluations. We do not judge that our servant has a superior moral character, and we do not automatically conclude that those who live in our own country are morally superior to those living in foreign countries (T 3.3.1.14). So, Hume needs some explanation of why our considered moral evaluations do not match our immediate feelings.

Hume responds by explaining that, when judging the quality of someone’s character, we adopt a perspective that discounts our specific spatial-temporal location or any other special resemblance we might have with the person being evaluated. Hume tells us that this vantage point is one in which we consider the influence that the person in question has upon his or her contemporaries (T 3.3.3.2). When we evaluate Brutus’ character, we do not consider the influence that his qualities have upon us now. As a historical figure who no longer exists, Brutus’ virtuous character does not provide any present benefit. Instead, we evaluate Brutus’ character based upon the benefits it had for those who lived in Brutus’ own time. We recognize that if we had lived in Brutus’ own time, and were a fellow Roman citizen with him, then we would express much greater praise and admiration for his character (T 3.3.1.16).

Hume identifies a second type of correction that the general point of view is responsible for as well. Hume observes that we have the capacity to praise someone whose character traits are widely beneficial, even when unfortunate external circumstances prevent those traits from being effective (T 3.3.1.19). For example, we might imagine a generous, kind-hearted individual whose generosity fails to make much of an impact on others because she is of modest means. Hume claims, in these cases, our considered moral evaluation is not influenced by such external circumstances: “Virtue in rags is still virtue” (T 3.3.1.19). At the same time, we might be puzzled how this could be the case since we naturally give stronger praise to the person whose good fortune enables her virtuous traits to produce actual benefits (T 3.3.1.21). Hume makes a two-fold response here. First, because we know that (for instance) a generous character is often correlated with benefits to society, we establish a “general rule” that links these together (T 3.3.1.20). Second, when we take up the general point of view, we ignore the obstacles of misfortune that prevent this virtuous person’s traits from achieving their intended goal (T 3.3.1.21). Just as we discount spatial-temporal proximity, so we also discount the influence of fortune when making moral evaluations of another’s character traits.

So, adopting the general point of view requires spectators to set aside a multitude of considerations: self-interest, demographic resemblance, spatial-temporal proximity, and the influence of fortune. What motivates us to adopt this vantage point? Hume explains that doing so enables us to discuss the evaluations we make of others. If we each evaluated from our personal perspective, then a character that garnered the highest praise from me might garner only than mild praise from you. The general point of view, then, provides a common basis from which differently situated individuals can arrive at some common understanding of morality (T 3.3.1.15). Still, Hume notes that this practical solution may only regulate our language and public judgments of our peers. Our personal feelings often prove too entrenched. When our actual sentiments are too resistant to correction, Hume notes that we at least attempt to conform our language to the objective standard (T 3.3.1.16).

In addition to explaining why it is that we adopt the general point of view, one might also think that Hume owes us an explanation of why this perspective constitutes the standard of correctness for moral evaluation. In one place Hume states that the “corrections” we make to our sentiments from the general point of view are “alone regarded, when we pronounce in general concerning the degrees of vice and virtue” (T 3.3.1.21). Nine paragraphs later Hume again emphasizes that the sentiments we feel from the general point of view constitute the “standard of virtue and morality” (T 3.3.1.30). What gives the pronouncements we make from the general point of view this authoritative status?

Hume scholars are divided on this point. One possibility, developed by Geoffrey Sayre-McCord, is that adopting the general point of view enables us to avoid the practical conflicts that inevitably arise when we judge character traits from our individual perspectives (Sayre-McCord 1994: 213-220). Jacqueline Taylor, focusing primarily on the second Enquiry, argues that the normative authority of the general point of view arises from the fact that it arises from a process of social deliberation and negotiation requiring the virtues of good judgment (Taylor 2002). Rachel Cohon argues that evaluations issuing from the general point of view are most likely to form true ethical beliefs (Cohon 2008: 152-156). In a somewhat similar vein, Kate Abramson argues that the general point of view enables us to correctly determine whether some character trait enables its possessor to act properly within the purview of her relationships and social roles (Abramson 2008: 253). Finally, Phillip Reed argues that, to the contrary, the general point of view does not constitute Hume’s “standard of virtue” (Reed 2012).

3. Sympathy and Humanity

a. Sympathy

We have seen that, for Hume, a sentiment can qualify as a moral sentiment only if it is not the product of pure self-interest. This implies that human nature must possess some capacity to get outside of itself and take an interest in the fortunes and misfortunes of others. When making moral evaluations we approve qualities that benefit the possessor and her associates, while disapproving of those qualities that make the possessor harmful to herself or others (T 3.3.1.10). This requires that we can take pleasure in that which benefits complete strangers. Thus, moral evaluation would be impossible without the capacity to partake of the pleasure (or pain) of any being that shares our underlying human nature. Hume identifies “sympathy” as the capacity that makes moral evaluation possible by allowing us to take an interest in the public good (T 3.3.1.9). The idea that moral evaluation is based upon sympathy can also be found in the work of Hume’s contemporary Adam Smith (1723-1790). However, the account of sympathy found in Smith’s work also differs in important ways from what we find in Hume.

Because of the central role that sympathy plays in Hume’s moral theory, his account of sympathy deserves further attention. Hume tells us that sympathy is the human capacity to “receive” the feelings and beliefs of other people (T 2.1.11.2). That is, it is the process by which we experience what others are feeling and thinking. This process begins by forming an idea of what another person is experiencing. This idea might be formed through observing the effects of another’s feeling (T 2.1.11.3). For instance, from my observation that another person is smiling, and my prior knowledge that smiling is associated with happiness, I form an idea of the other’s happiness. My idea of another’s emotion can also be formed prior to the other person feeling the emotion. This occurs through observing the usual causes of that emotion. Hume provides the example of someone who observes surgical instruments being prepared for a painful operation. He notes that this person would feel terrified for the person about to suffer through the operation even though the operation had not yet begun (T 3.3.1.7). This is because the observer already established a prior mental association between surgical instruments and pain.

Since sympathy causes us to feel the sentiments of others, simply having an idea of another’s feeling is insufficient. That idea must be converted into something with more affective potency. Our idea of what another feels must be transformed into an impression (T 2.1.11.3). The reason this conversion is possible is that the only difference between impressions and ideas is the intensity with which they are felt in the mind (T 2.1.11.7). Recall that impressions are the most forceful and intense whereas ideas are merely “faint images” of our impressions (T 1.1.1.1). Hume identifies two facts about human nature which explain what causes our less vivacious idea of another’s passion to be converted into an impression and, notably, become the very feeling the other is experiencing (T 2.1.11.3). First, we always experience an impression of ourselves which is not surpassed in force, vivacity, and liveliness by any other impression. Second, because we have this lively impression of ourselves, Hume believes it follows that whatever is related to that impression must receive some share of that vivacity (T 2.1.11.4). From these points, it follows that our idea of another’s impression will be enlivened if that idea has some relation to ourselves.

Hume explains the relationship between our idea of another’s emotion and ourselves in terms of his more general conception of how the imagination produces associations of ideas. Hume understands the association of ideas as a “gentle force” that explains why certain mental perceptions repeatedly occur together. He identifies three such ways in which ideas become associated: resemblance (the sharing of similar characteristics), contiguity (proximity in space or time), and causation (roughly, the constant conjunction of two ideas in which one idea precedes another in time) (T 1.1.4.1). Hume appeals to each of these associations to explain the relationship between our idea of another’s emotion and our impression of self (T 2.1.11.6). However, resemblance plays the most important role. Although each individual human is different from one another, there is also an underlying commonality or resemblance within all members of the human species (T 2.1.11.5). For example, when we form an idea of another’s happiness, we implicitly recognize that we ourselves are also capable of that same feeling. That idea of happiness, then, becomes related to ourselves and, consequently, receives some of the vivacity that is held by the impression of our self. In this way, our ideas of how others feel become converted into impressions and we “feel with” our fellow human beings.

Although sympathy makes it possible for us to care for others, even those we have no close or immediate connection with, Hume acknowledges that it does not do so in an entirely impartial or egalitarian manner. The strength of our sympathy is influenced both by the universal resemblance that exists among all human beings as well as more parochial types of resemblances. We will sympathize more easily with those who share various demographic similarities such as language, culture, citizenship, or place of origin (T 2.1.11.5). Consequently, when the person we are sympathizing with shares these similarities we will form a stronger conception of their feelings, and when such similarities are absent our conception of their feeling will be comparatively weaker. Likewise, we will have stronger sympathy with those who live in our own city, state, country, or time, than we will with those who are spatially or temporally distant. In fact, it is this aspect of sympathy which prompts Hume to introduce the general point of view (discussed above). It is our natural sympathy that causes us to give stronger praise those who exist in closer spatial-temporal proximity, even though our considered moral evaluations do not exhibit such variation. Hume poses this point as an objection to his claim that our moral evaluations proceed from sympathy (T 3.3.1.14). Hume’s appeal to the general point of view allows him to respond to this objection. Moral evaluations arise from sympathetic feelings that are corrected by the influence of the general point of view.

b. Humanity

While sympathy plays a crucial role in Hume’s moral theory as outlined in the Treatise, explicit mentions of sympathy are comparatively absent from the Enquiry. In place of Hume’s detailed description of sympathy, we find Hume appealing to the “principle of humanity” (EPM 9.6). He understands this as the human disposition that produces our common praise for that which benefits the public and common blame for that which harms the public (EPM 5.39). The principle of humanity explains why we prefer seeing things go well for our peers instead of seeing them go badly. It also explains why we would not hope to see our peers suffer if that suffering in no way benefited us or satisfied our resentment from a prior provocation (EPM 5.39). Like sympathy, then, Hume uses humanity to explain our concern for the well-being of others. However, Hume’s discussion of humanity in the Enquiry does not appeal (at least explicitly) to the cognitive mechanism that underlies Hume’s account of sympathy, and he even expresses skepticism about the possibility of explaining this mechanism. So, the Enquiry does not discuss how our idea of another’s pleasures and pains is converted into an impression. This does not necessarily mean that sympathy is absent from the Enquiry. For instance, in Enquiry Section V Hume describes having the feelings of others communicated to us (EPM 5.18) and details how sharing our sentiments in a social setting can strengthen our feelings (EPM 5.24, EPM 5.35).

As he did with sympathy in the Treatise, Hume argues that the principle of humanity makes moral evaluations possible. It is because we naturally approve of that which benefits society, and disapprove of that which harms society, that we see some character traits as virtuous and others as vicious. Hume’s justification for this claim follows from his rejection of the egoists (EPM 5.6). Here Hume has in mind those like Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and Bernard Mandeville (1670-1733), who each believed that our moral judgments are the product of self-interest. Those qualities we consider virtuous are those that serve our interests, and those that we consider vicious are those that do not serve our interests. Hume gives a variety of arguments against this position. He contends that egoism cannot explain why we praise the virtues of historical figures (EPM 5.7) or recognize the virtues of our enemies (EPM 5.8). If moral evaluations are not the product of self-interest, then Hume concludes that they must be caused by some principle which gives us real concern for others. This is the principle of humanity. Hume admits that the sentiments produced by this principle might often be unable to overpower the influence that self-interest has on our actions. However, this principle is strong enough to give us at least a “cool preference” for that which is beneficial to society, and provides the foundation upon which we distinguish the difference between virtue and vice (EPM 9.4).

4. Hume’s Classification of the Virtues and the Standard of Virtue

Since Hume thinks virtuous qualities benefit society, while vicious qualities harm society, one might conclude that Hume should be placed within the utilitarian moral tradition. While Hume’s theory has utilitarian elements, he does not think evaluations of virtue and vice are based solely upon considerations of collective utility. Hume identifies four different “sources” of moral approval, or four different effects of character traits that produce pleasure in spectators (T 3.3.1.30). Hume generates these categories by combining two different types of benefits that traits can have (usefulness and immediate agreeability) with two different types of benefactor that a trait can have (the possessor of the trait herself and other people) (EPM 9.1). Below is an outline of the four resulting sources of moral approval.

- We praise traits that are useful to others. For example, justice (EPM 3.48) and benevolence (EPM 2.22).

- We praise traits that are useful to the possessor of the trait. For example, discretion or caution (EPM 6.8), industry (EPM 6.10), frugality (EPM 6.11), and strength of mind (EPM 6.15).

- We praise traits with immediate agreeability to others. For example, good manners (EPM 8.1) and the ability to converse well (EPM 8.5).

- We praise traits that are immediately agreeable to the possessor. For example, cheerfulness (EPM 7.2) and magnanimity (EPM 7.4-7.18).

What does Hume mean by “immediate agreeability”? Hume explains that immediately agreeable traits please (either the possessor or others) without “any further thought to the wider consequences that trait brings about” (EPM 8.1). Although being well-mannered has beneficial long-term consequences, Hume believes we also praise this trait because it is immediately pleasing to company. As we shall see below, this distinction implies that a trait can be praised for its immediate agreeability even if the trait has harmful consequences more broadly.

There is disagreement amongst Hume scholars about how this classification of virtue is related to Hume’s definition of what constitutes a virtue, or what is termed the “standard of virtue.” That is, what is the standard which determines whether some character trait counts as a virtue? The crux of this disagreement can be found in two definitions of virtue that Hume provides in the second Enquiry.

First Definition: “personal merit consists altogether in the possession of mental qualities, useful or agreeable to the person himself or to others” (EPM 9.1).

Second Definition: “It is the nature, and, indeed, the definition of virtue, that it is a quality of the mind agreeable to or approved of by every one who considers or contemplates it” (EPM 8.n50).

The first definition suggests that virtue is defined in terms of its usefulness or agreeableness. On this basis, we might interpret Hume as believing that a trait fails to qualify as a virtue if it is neither useful nor agreeable. This interpretation is also supported by places in the text where Hume criticizes approval of traits that fail to meet the standard of usefulness and agreeableness. One prominent example is his discussion of the religiously motivated “monkish virtues.” There he criticizes those who praise traits such as “[c]elibacy, fasting, penance, mortification, self-denial, humility, silence, solitude” on the grounds that these traits are neither useful to society nor agreeable to their possessors (EPM 9.3). The second definition, however, holds that what determines whether some character trait warrants the status of virtue is the ability of that trait to generate spectator approval. On this view, some trait is a virtue if it garners approval from a general point of view, and the sources of approval (usefulness and agreability) simply describe those features of character traits that human beings find praiseworthy.

5. Justice and the Artificial Virtues

The four-fold classification of virtue discussed above deals with the features of character traits that attract our approval (or disapproval). However, in the Treatise Hume’s moral theory is primarily organized around a distinction between the way we approve (or disapprove) of some character trait. Hume tells us that some virtues are “artificial” whereas other virtues are “natural” (T 3.1.2.9). In this context, the natural-artificial distinction tracks whether the entity in question results from the plans or designs of human beings (T 3.1.2.9). On this definition, a tree would be natural whereas a table would be artificial. Unlike the former, the latter required some process of human invention and design. Hume believes that a similar type of distinction is present when we consider different types of virtue. There are natural virtues like benevolence, and there are artificial virtues like justice and rules of property. In addition to justice and property, Hume also classifies the keeping of promises (T 3.1.2.5), allegiance to government (T 3.1.2.8), laws of international relations (T 3.1.2.11), chastity (T 3.1.2.12), and good manners (T 3.1.2.12) as artificial virtues.

The designs that constitute the artificial virtues are social conventions or systems of cooperation. Hume describes the relationship between artificial virtues and their corresponding social conventions in different ways. The basic idea is that we would neither have any motive to act in accordance with the artificial virtues (T 3.2.1.17), nor would we approve of artificially virtuous behavior (T 3.2.1.1), without the relevant social conventions. No social scheme is needed for us to approve of an act of kindness. However, the very existence of people who respect property rights, and our approval of those who respect property rights, requires some set of conventions that specify rules regulating the possession of goods. As we will see, Hume believes the conventions of justice and property are based upon collective self-interest. In this way, Hume uses the artificial-natural virtue distinction to carve out a middle position in the debate between egoists (like Hobbes and Mandeville), who believe that morality is a product of self-interest, and moral sense theorists (like Shaftesbury and Hutcheson), who believe that our sense of virtue and vice is natural to human nature. The egoists are right that some virtues are the product of collective self-interest (the artificial virtues), but the moral sense theorists are also correct insofar as other virtues (the natural virtues) have no relation to self-interest.

a. The Circle Argument

In Treatise 3.2.1 Hume provides an argument for the claim that justice is an artificial virtue (T 3.2.1.1). Understanding this argument requires establishing three preliminary points. First, Hume uses the term “justice,” at least in this context, to refer narrowly to the rules that regulate property. So, his purpose here is to prove that the disposition to follow the rules of property is an artificial virtue. That is, it would make no sense to approve of those who are just, nor to act justly, without the appropriate social convention. Second, Hume uses the concept of a “mere regard to the virtue of the action” (T 3.2.1.4) or a “sense of morality or duty” (T 3.2.1.8). This article uses the term “sense of duty.” The sense of duty is a specific type of moral motivation whereby someone performs a virtuous action only because she feels it is her ethical obligation to do so. For instance, imagine that someone has a job interview and knows she can improve her chances of success by lying to the interviewers. She might still refrain from lying, not because this is what she desires, but because she feels it is her moral obligation. She has, thus, acted from a sense of duty.

Third, a crucial step in Hume’s argument involves showing that a sense of duty cannot be the “first virtuous motive” to justice (T 3.2.1.4). What does it mean for some motive to be the “first motive?” It is tempting to think that Hume uses the phrase “first motive” as a synonym for “original motive.” Original motives are naturally present in the “rude and more natural condition” of human beings prior to modern social norms, rules, and expectations (T 3.2.1.9). For example, parental affection provides an original motive to care for one’s children (T 3.2.1.5). As we will see, Hume does not believe that the sense of duty can be an original motive to justice. One can only act justly from a sense of duty after some process of education, training, or social conditioning (T 3.2.1.9). However, while Hume does believe that many first motives are original in human nature, it cannot be his position that all first motives are original in human nature. This is because he does not believe there is any original motive to act justly, but he does think there is a first motive to act justly. Therefore, it is best to understand Hume’s notion of the first motive to perform some action as whatever motive (whether original or arising from convention) first causes human beings to perform that action.

With these points in place, let us consider the basic structure of Hume’s reasoning. His fundamental claim is that there is no original motive that can serve as the first virtuous motive of just actions. That is, there is nothing in the original state of human nature, prior to the influence of social convention, that could first motivate someone to act justly. While in our present state a “sense of duty” can serve as a sufficient motive to act justly, human beings in our natural condition would be bewildered by such a notion (T 3.2.1.9). However, if no original motive can be found that first motivates justice, then it follows that justice must be an artificial virtue. This is implied from Hume’s definition of artificial virtue. If the first motive for some virtue is not an original motive, then that virtue must be artificial.

Against Hume, one might argue that human beings have a natural “sense of justice” and that this serves as an original motive for justice. Hume rejects this claim with an argument commonly referred to as the “Circle Argument.” The foundation of this argument is the previously discussed claim that when making a moral evaluation of an action, we are evaluating the motive, character trait, or disposition that produced that action (T 3.2.1.2). Hume points out that we often retract our blame of another person if we find out they had the proper motive, but they were prevented from acting on that motive because of unfortunate circumstances (T 3.2.1.3). Imagine a good-hearted individual who gives money to charity. Suppose also that, through no fault of her own, her donation fails to help anyone because the check was lost in the mail. In this case, Hume argues, we would still praise this person even though her donation was not beneficial. It is the willingness to help that garners our praise. Thus, the moral virtue of an action must derive completely from the virtuous motive that produces it.

Now, assume for the sake of argument that the first virtuous motive of some action is a sense of duty to perform that action. What would have to be the case for a sense of duty to be a virtuous motive that is worthy of praise? At minimum, it would have to be true that the action in question is already virtuous (T 3.2.1.4). It would make no sense to claim that there is a sense of duty to perform action X, but also hold that action X is not virtuous. Unfortunately, this brings us back to where we began. If action X is already virtuous prior to our feeling any sense of duty to perform it, then there must likewise already be some other virtuous motive that explains action X’s status as a virtue. Thus, since some other motive must already be able to motivate just actions, a sense of duty cannot be the first motive to justice. Therefore, our initial assumption causes us to “reason in a circle” (T 3.2.1.4) and, consequently, must be false. From this, it follows that an action cannot be virtuous unless there is already some motive in human nature to perform it other than our sense, developed later, that performing the action is what is morally right (T 3.2.1.7). The same, then, would hold for the virtue of justice. This does not mean that a sense of duty cannot motivate us to act justly (T 3.2.1.8), nor does it necessarily mean that a sense of duty cannot be a praiseworthy motive. Hume’s point is simply that a sense of duty cannot be what first motivates us to act virtuously.

Having dispensed with the claim that a sense of duty can be an original motive, Hume then considers (and rejects) three further possible candidates of original motives that one might claim could provide the first motive to justice. These are: (i) self-interest, (ii) concern for the public interest, (iii) concern for the interests of the specific individual in question. Hume does not deny that each of these are original motives in human nature. Instead, he argues that none of them can adequately account for the range of situations in which we think one is required to act justly. Hume notes that unconstrained self-interest causes injustice (T 3.2.1.10), that there will always be situations in which one can act unjustly without causing any serious harm to the public (T 3.2.1.11), and that there are situations in which the individual concerned will benefit from us acting unjustly toward her. For example, this individual could be a “profligate debauchee” who would only harm herself by keeping her possessions (T 3.2.1.13). Consequently, if there is no original motive in human nature that can produce just actions, it must be the case that justice is an artificial virtue.

b. The Origin of Justice

Thus far Hume has established that justice is an artificial virtue, but has still not identified the “first motive” of justice. Hume begins to address this point in the next Treatise section entitled “Of the origin of justice and property.” We will see, however, that Hume’s complete account of what motivates just behavior goes beyond his comments here. Hume begins his account of the origin of justice by distinguishing two questions.

Question 1: What causes human beings in their natural, uncultivated state to form conventions that specify property rights? That is, how do the conventions of justice arise?

Question 2: Once the conventions of justice are established, why do we consider it a virtue to follow the rules specified by those conventions? In other words, why is justice a virtue?

Answering Question 1 requires determining what it is about the “natural” human condition (prior to the establishment of modern, large-scale society) that motivates us to construct the specific rules, norms, and social expectations associated with justice. Hume does this by outlining an account of how natural human beings come to recognize the benefits of establishing and preserving practices of cooperation.

Hume begins by claiming that the human species has many needs and desires it is not naturally equipped to meet (T 3.2.2.2). Human beings can only remedy this deficiency through societal cooperation that provides us with greater power and protection from harm than is possible in our natural state (T 3.2.2.3). However, natural humans must also become aware that societal cooperation is beneficial. Fortunately, even in our “wild uncultivated state,” we already have some experience of the benefits that are produced through cooperation. This is because the natural human desire to procreate, and care for our children, causes us to form family units (T 3.2.2.4). The benefits afforded by this smaller-scale cooperation provide natural humans with a preview of the benefits promised by larger-scale societal cooperation.

Unfortunately, while our experience with living together in family units shows us the benefits of cooperation, various obstacles remain to establishing it on a larger scale. One of these comes from familial life itself. The conventions of justice require us to treat others equally and impartially. Justice demands that we respect the property rights of those we love and care for just as we respect the property rights of those whom we do not know. Yet, family life only strengthens our natural partiality and makes us place greater importance on the interests of our family members. This threatens to undermine social cooperation (T 3.2.2.6). For this reason, Hume argues that we must establish a set of rules to regulate our natural selfishness and partiality. These rules, which constitute the conventions of justice, allow everyone to use whatever goods we acquire through our labor and good fortune (T 3.2.2.9). Once these social norms are in place, it then becomes possible to use terms such as “property, right, [and] obligation” (T 3.2.2.11).

This account further supports Hume’s claim that justice is an artificial virtue. Justice remedies specific problems that human beings face in their natural state. If circumstances were such that those problems never arose, then the conventions of justice would be pointless. Certain background conditions must be in place for justice to originate. John Rawls (1921-2002) refers to these conditions as the “circumstances of justice” (Rawls 1971: 126n). The remedy of justice is required because the goods we acquire are vulnerable to being taken by others (T 3.2.2.7), resources are scarce (T 3.2.2.7), and human generosity is limited (T 3.2.2.6). Regarding scarcity and human generosity, Hume explains that our circumstances lie at a mean between two extremes. If resources were so prevalent that there were enough goods for everyone, then there would be no reason to worry about theft or establish property rights (EPM 3.3). On the other hand, if scarcity were too extreme, then we would be too desperate to concern ourselves with the demands of justice. Nobody worries about acting justly after a shipwreck (EPM 3.8). In addition, if humans were characterized by thoroughgoing generosity, then we would have no need to restrain the behavior of others through rules and restrictions (EPM 3.6). By contrast, if human beings were entirely self-interested, without any natural concern for others, then there could be no expectation that others would abide by any rules that are established (EPM 3.9). Justice is only possible because human life is not characterized by these extremes. If human beings were characterized by universal generosity, then justice could be replaced with “much nobler virtues, and more valuable blessings” (T 3.2.2.16).

Another innovative aspect of Hume’s theory is that he does not believe the conventions of justice are based upon promises or explicit agreements. This is because Hume believes that promises themselves only make sense if certain human conventions are already established (T 3.2.2.10). Thus, promises cannot be used to explain how human beings move from their natural state to establishing society and social cooperation. Instead, Hume explains that the conventions of justice arise from “a general sense of common interest” (T 3.2.2.10) and that cooperation can arise without explicit agreement. Once it is recognized that everyone’s interest is served when we all refrain from taking the goods of others, small-scale cooperation becomes possible (T 3.2.2.10). In addition to allowing for a sense of security, cooperation serves the common good by enhancing our productivity (T 3.2.5.8). Our understanding of the benefits of social cooperation becomes more acute by a gradual process through which we steadily gain more confidence in the reliability of our peers (T 3.2.2.10). None of this requires an explicit agreement or promise. He draws a comparison with how two people rowing a boat can cooperate by an implicit convention without an explicit promise (T 3.2.2.10).

Although the system of norms that constitutes justice is highly advantageous and even necessary for the survival of society (T 3.2.2.22), this does not mean that society gains from each act of justice. An individual act of justice can make the public worse off than it would have otherwise been. For example, justice requires us to pay back a loan to a “seditious bigot” who will use the money destructively or wastefully (T 3.2.2.22). Artificial virtues differ from the natural virtues in this respect (T 3.3.1.12). This brings us to Hume’s second question about the virtue of justice. If not every act of justice is beneficial, then why do we praise obedience to the rules of justice? The problem is especially serious for large, modern societies. When human beings live in small groups the harm and discord caused by each act of injustice is obvious. Yet, this is not the case in larger societies where the connection between individual acts of justice and the common good is much weaker (T 3.2.2.24).

Consequently, Hume must explain why we continue to condemn injustice even after society has grown larger and more diffuse. On this point Hume primarily appeals to sympathy. Suppose you hear about some act of injustice that occurs in another city, state, or country, and harms individuals you have never met. While the bad effects of the injustice feel remote from our personal point of view, Hume notes that we can still sympathize with the person who suffers the injustice. Thus, even though the injustice has no direct influence upon us, we recognize that such conduct is harmful to those who associate with the unjust person (T 3.2.2.24). Sympathy allows our concern for justice to expand beyond the narrow bounds of the self-interested concerns that first produced the rules.

Thus, it is self-interest that motivates us to create the conventions of justice, and it is our capacity to sympathize with the public good that explains why we consider obedience to those conventions to be virtuous (T 3.2.2.24). Furthermore, we can now better understand how Hume answers the question of what first motivates us to act justly. Strictly speaking, the “first motive” to justice is self-interest. As noted previously, it was in the immediate interest of early humans living in small societies to comply with the conventions of justice because the integrity of their social union hinged upon absolute fidelity to justice. As we will see below, this is not the case in larger, modern societies. However, all that is required for some motive to be the first motive to justice is that it is what first gives humans some reason to act justly in all situations. The fact that this precise motive is no longer present in modern society does not prevent it from being what first motivates such behavior.

c. The Obligation of Justice and the Sensible Knave

Given that justice is originally founded upon considerations of self-interest, it may seem especially difficult to explain why we consider it wrong of ourselves to commit injustice in larger modern societies where the stakes of non-compliance are much less severe. Here Hume believes that general rules bridge the gap. Hume uses general rules as an explanatory device at numerous points in the Treatise. For example, he explains our propensity to draw inferences based upon cause and effect through the influence of general rules (T 1.3.13.8). When we consistently see one event (or type of event) follow another event (or type of event), we automatically apply a general rule that makes us expect the former whenever we experience the latter. Something similar occurs in the present context. Through sympathy, we find that sentiments of moral disapproval consistently accompany unjust behavior. Thus, through a general rule, we apply the same sort of evaluation to our own unjust actions (T 3.2.2.24).

Hume believes our willingness to abide by the conventions of justice is strengthened through other mechanisms as well. For instance, politicians encourage citizens to follow the rules of justice (T 3.2.2.25) and parents encourage compliance of their children (T 3.2.2.26). Thus, the praiseworthy motive that underlies compliance with justice in large-scale societies is, to a large extent, the product of social conditioning. This fact might make us suspicious. If justice is an artificial virtue, and if much of our motivation to follow its rules comes from social inculcation, then we might wonder whether these rules deserve our respect.

Hume recognizes this issue. In the Treatise he briefly appeals to the fact that having a good reputation is largely determined by whether we follow the rules of property (T 3.2.2.27). Theft, and the unwillingness to follow the rules of justice, does more than anything else to establish a bad reputation for ourselves. Furthermore, Hume claims that our reputation in this regard requires that we see each rule of justice as having absolute authority and never succumb when we are tempted to act unjustly (T 3.2.2.27). Suppose Hume is right that our moral reputation hangs on our obedience to the rules of justice. Even if true, it is not obvious that this requires absolute obedience to these rules. What if I can act unjustly without being detected? What if I can act unjustly without causing any noticeable harm? Is there any reason to resist this temptation?

Hume takes up this question directly in the Enquiry, where he considers the possibility of a “sensible knave.” The knave recognizes that, in general, justice is crucial to the survival of society. Yet, the knave also recognizes that there will always be situations in which it is possible to act unjustly without harming the fabric of social society. So, the knave follows the rules of justice when he must, but takes advantage of those situations where he knows he will not be caught (EPM 9.22). Hume responds that, even if the knave is never caught, he will lose out on a more valuable form of enjoyment. The knave forgoes the ability to reflect pleasurably upon his own conduct for the sake of material gain. In making this trade, Hume judges that knaves are “the greatest dupes” (EPM 9.25). The person who has traded the peace of mind that accompanies virtue in order to gain money, power, or fame has traded away that which is more valuable for something much less valuable. The enjoyment of a virtuous character is incomparably greater than the enjoyment of whatever material gains can be attained through injustice. Thus, justice is desirable from the perspective of our own personal happiness and self-interest (EPM 9.14).

Hume admits it will be difficult to convince genuine knaves of this point. That is, it will be difficult to convince someone who does not already value the possession of a virtuous character that justice is worth the cost (EPM 9.23). Thus, Hume does not intend to provide a defense of justice that can appeal to any type of being or provide a reason to be just that makes sense to “all rational beings.” Instead, he provides a response that should appeal to those with mental dispositions typical of the human species. If the ability to enjoy a peaceful review of our conduct is nearly universal in the human species, then Hume will have provided a reason to act justly that can make some claim upon nearly every human being.

6. The Natural Virtues

After providing his Treatise account of the artificial virtues, Hume moves to a discussion of the natural virtues. Recall that the natural virtues, unlike the artificial virtues, garner praise without the influence of any human convention. Hume divides the natural virtues into two broad categories: those qualities that make a human great and those that make a human good (T 3.3.3.1). Hume consistently associates a cluster of qualities with each type of character. The great individual is confident, has a sense of her value, worth, or ability, and generally possesses qualities that set her apart from the average person. She is courageous, ambitious, able to overcome difficult obstacles, and proud of her achievements (EPM 7.4, EPM 7.10). By contrast, the good individual is characterized by gentle concern for others. This person has the types of traits that make someone a kind friend or generous philanthropist (EPM 2.1). Elsewhere, Hume explains the distinction between goodness and greatness in terms of the relationship we would want to have with the good person or the great person: “We cou’d wish to meet with the one character in a friend; the other character we wou’d be ambitious of in ourselves” (T 3.3.4.2).

Alexander of Macedonia exemplifies an extreme case of greatness. Hume recounts how Alexander responded when his general Parmenio suggested he accept the peace offering made by the Persian King Darius III. When Parmenio advises Alexander to accept Darius’ offering, Alexander responds that “So would I too […] were I Parmenio” (EPM 7.5). There are certain constraints that apply to the average person that Alexander does not think apply to himself. This is consistent with the fact that the great individual has a strong sense of self-worth, self-confidence, and even a sense of superiority.

a. Pride and Greatness of Mind

Given the characteristics Hume associates with greatness, it should not be a surprise that Hume begins the Treatise section entitled “Of Greatness of Mind” by discussing pride (T 3.3.2). Those qualities and accomplishments that differentiate one from the average person are also those qualities most likely to make us proud and inspire confidence. Thus, Hume notes that pride forms a significant part of the hero’s character (T 3.3.2.13). However, Hume faces a problem—how can a virtuous character trait be based upon pride? He observes that we blame those who are too proud and praise those with enough modesty to recognize their own weaknesses (T 3.3.2.1). If we commonly find the pride of others disagreeable, then why do we praise the boldness, confidence, and prideful superiority of the great person?

Hume must explain when pride is praiseworthy, and when it is blameworthy. In part, Hume believes expressions of pride become disagreeable when the proud individual boasts about qualities she does not possess. This results from an interplay between the psychological mechanisms of sympathy and comparison. Sympathy enables us to adopt the feelings, sentiments, and opinions of other people and, consequently, participate in that which affects another person. Comparison is the human propensity for evaluating the situation of others in relation to ourselves. It is through comparison that we make judgments about the value of different states of affairs (T 3.3.2.4). Notice that sympathy and comparison are each a stance or attitude we can take toward those who are differently situated. For example, if another individual has secured a desirable job opportunity (superior to my own), then I might sympathize with the benefits she reaps from her employment and participate in her joy. Alternatively, I might also compare the benefits and opportunities her job affords with my own lesser situation. The result of this would be a painful feeling of inferiority or jealousy. Thus, each of these mechanisms has an opposite tendency (T 3.3.2.4).